At the IHR Parliaments, Politics and People seminar on Tuesday 11 November, Steven Spencer of Birkbeck, University of London, will be discussing the campaign to pass the 1885 Criminal Law Amendment Act.

The seminar takes place on 11 November 2025, between 5:30 and 6:30 p.m. It is fully ‘hybrid’, which means you can attend either in-person in London at the IHR, or online via Zoom. Details of how to join the discussion are available here.

In 1881 the House of Lords select committee on the law relating to the protection of young girls recommended the passage of a criminal law amendment bill. The bill proposed raising the age of consent from 13, increasing the power of the police over brothels and criminalising acts of what it called ‘gross indecency’ between men. Despite passing repeatedly through the Lords, the legislation twice failed to pass through the House of Commons in the face of parliamentary inertia.

![A section of a page from the 1885 Criminal Law Amendment Act which reads: 'Chapter 69. An act to make further provision for the Protection of Women and Girls, the suppression of brothels, and other purposes. [14th August 1885.] Be it enacted by the Queen's most excellent Majesty, by and with the advice and consent of the Lords Spiritual and Temporal, and Commons, in this present Parliament assembled, and by the aurhority of the same, as follows: 1. This Act may be cited as the Criminal Law Amendment Act, 1885.'](http://hopblog.monaghan.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/1885-CLAACT.png)

A campaign to win popular support for raising the age of consent as a means of combating juvenile prostitution had been promoted by the social purity movement from the 1870s. The movement advocated for a single standard of morality between men and women. Its members included Alfred Dyer, who highlighted the traffic of English women to European brothels, and Ellice Hopkins who founded both the Church of England Purity Society and the working-class White Cross Army. Dyer’s journal The Sentinel was the official organ of the social purity movement, which had grown out of the success of the campaign to repeal the Contagious Diseases Acts of the 1860s, led by Josephine Butler. Butler had set up the first purity association, the Social Purity Alliance, in 1873.

The Contagious Diseases Acts (the first of which passed in 1864) covered certain areas of the UK around military bases and gave the police powers to compel women suspected of being sex workers to be medically inspected for venereal disease and detained until they were cured. These acts were designed to control the spread of venereal disease within the armed forces but there was no equivalent compulsory examination or detention for men. The ultimately successful campaign for their repeal mobilised middle class women and gave them an unprecedented political voice.

The criminal law amendment bill failed to pass the House of Commons in 1883 and 1884, due primarily to extraordinary pressures on Gladstone’s Liberal government. These included the third reform bill, the Mahdist uprising and the very real prospect of war with Russia in 1885. The bill was also held up, in part, by conflict within the social purity movement, some of whom wanted to focus parliamentary time on the repeal of the Contagious Diseases Acts after they were suspended in 1883. One source of planned pressure on Parliament to pass the bill surrounded the revelatory trial of the high-class brothel keeper, Mary Jeffries, in May 1885. However, her unexpected guilty plea prevented the giving of evidence and the plan collapsed.

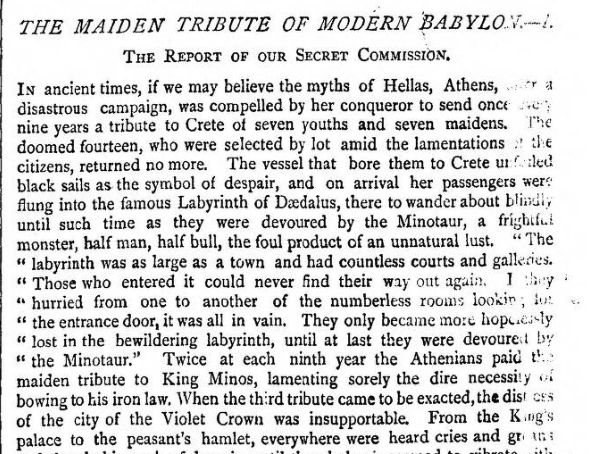

The next attempt to force the bill through Parliament was a series of sensational articles in the Pall Mall Gazette. This series, ‘The Maiden Tribute of Modern Babylon’, was written by the Gazette’s editor, W. T. Stead, over the course of a week in July 1885. The articles highlighted the issue of juvenile and coercive prostitution. They were the result of an investigation by a ‘secret commission’ headed by Stead and including members of the Salvation Army. He described the revelations in these articles as ‘abominable, unutterable, and worse than fables’.

Stead’s articles made repeated reference to Parliament and sometimes directly addressed Lord Salisbury’s new Conservative government, which had taken office a month earlier. The articles had to make a careful and considered appeal to legislators to achieve a change in the law, while also rousing public opinion about the ‘protection of women and girls’.

While the earlier failures of the bill to pass the Commons were mainly due to pressure on parliamentary time, during 1885 the likely success of the bill was bolstered by allegations that some MPs would be personally embarrassed by revelations in Stead’s articles in the Pall Mall Gazette. Josephine Butler commented that ‘there are guilty men on the Treasury bench who now begin to be most uneasy’.

Some MPs actively supported the bill. They were all Liberals and mainly Nonconformists in religion. These included Samuel Morley, Henry Broadhurst, Samuel Smith, James Stuart and James Stansfeld, who was a veteran of the Contagious Diseases Acts campaign. Two MPs, Morley and Richard Reid, sat on a committee of inquiry which verified the truth of W. T. Stead’s articles, alongside the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Catholic Cardinal Manning.

The Criminal Law Amendment Act was passed by Parliament in August 1885. The new Act raised the age of consent to 16, increased the power of the police over brothels and criminalised acts of ‘gross indecency’ between men. Clauses relating to the latter, which criminalised sexual activity between men, were added to the bill by the Liberal MP Henry Labouchere.

Following the Act, the social purity movement coalesced itself into the National Vigilance Association to ensure the legislation was effectively enforced. Their campaigns and subsequent police prosecutions would focus primarily on the anti-brothel legislation, rather than the age of consent clauses. The impact of the Criminal Law Amendment Act’s criminalisation of male homosexuality would continue to be felt until its partial repeal by the 1967 Sexual Offences Act.

SS

To find out more, Steven’s seminar takes place on 11 November 2025, between 5:30 and 6:30 p.m. It is fully ‘hybrid’, which means you can attend either in-person in London at the IHR, or online via Zoom. Details of how to join the discussion are available here.