‘Was the 1832 Reform Act “Great”?’ may not be the standard exam question it once was, but ongoing research about the Act’s broader legacy and impact on political culture, based on new resources and analytical techniques, continues to reshape our understanding of its place in modern British political development, as Dr Philip Salmon of our House of Commons, 1832-1945 project explains.

For a 20 minute talk about the Reform Act by Dr Philip Salmon please click here.

Much attention used to be focused on the number of voters enfranchised by the 1832 Reform Act. The extent to which the overall increase of around 314,000 electors in the UK (from around 11 to 18% of adult males) amounted to some form of democratic advance, however, has always been complicated by the Act’s limitations as an enfranchising measure, especially given the huge expectations aroused by the popular outdoors campaign in its support. Not only were most working-class voters excluded from the Act’s new occupier franchises, helping to inspire the important Chartist movement, but also many working-class electors were actually deprived of their former voting rights.

In Maldon, for example, the number of electors dropped from over 3,000 in 1831 to just 716 in 1832. This was owing to the Act’s new restrictions on non-resident voters, honorary freemen and freemen created by marriage. Abolishing the votes obtained by marrying a freeman’s daughter was an aspect of the Reform Act which evidently caused all sorts of problems in some boroughs. Similar reductions occurred in Lancaster (72%), Ludlow (64%), Bridgnorth (50%) and Sudbury (49%), as the History of Parliament‘s detailed constituency articles reveal.

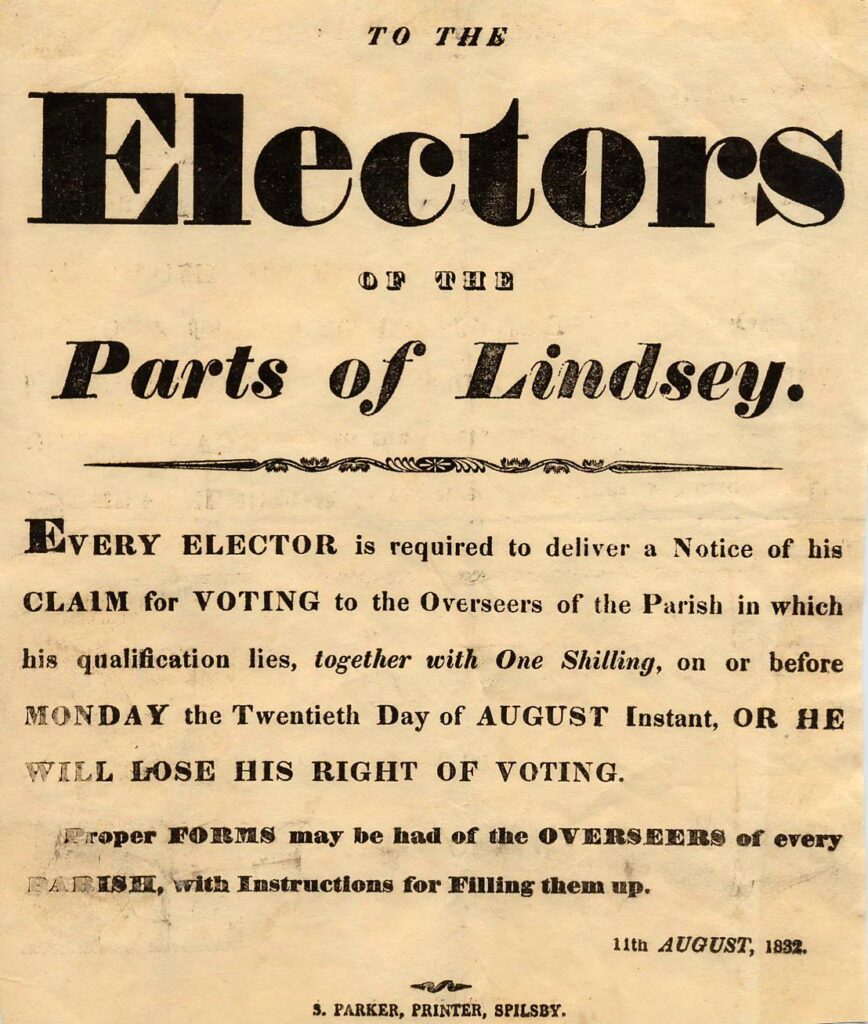

Add to this all the bureaucracy involved in the new yearly voter registration system – form filling, paying up arrears of rates, one shilling registration fees – and it is easy to see why so many people failed to benefit as expected from 1832. ‘Many doggedly refused to register’, noted one paper. ‘To the poor man’, complained another, ‘a shilling is a serious amount’. Taken as a whole, for every three new borough electors enfranchised by the 1832 Reform Act, at least one pre-1832 voter was deprived of their voting rights. Another restriction with lasting cultural connotations was the Act’s formal limitation of the franchise, for the first time, exclusively to ‘male persons‘.

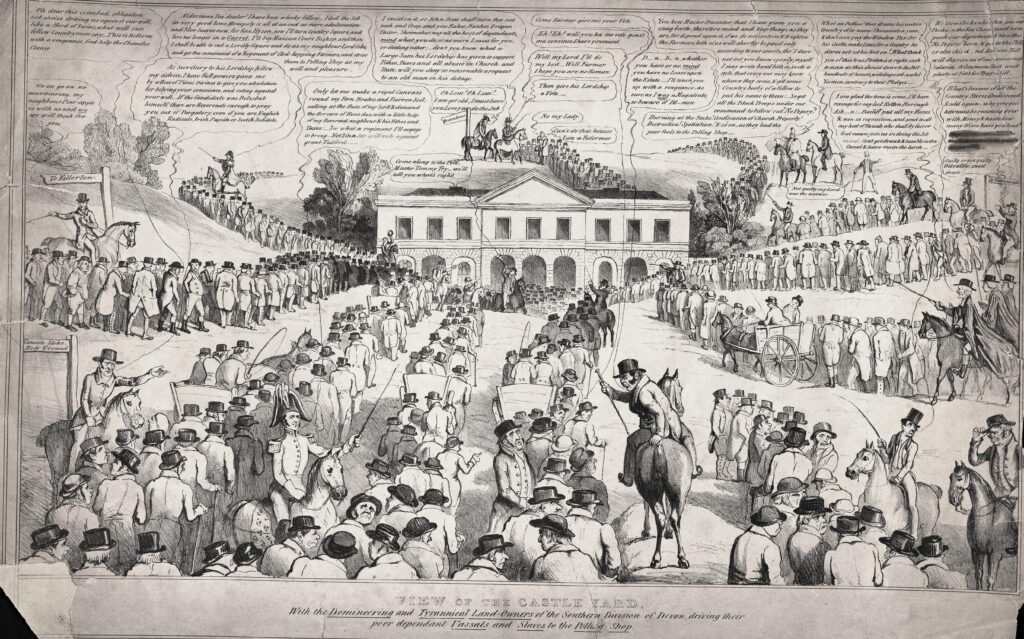

County voters faced fewer new restrictions, both in terms of continuing to exercise their old franchise (the 40 shilling freehold) even if they were non-resident, or claiming one of the new occupier (tenant, copyholder and leaseholder) franchises. But this did not make the impact of 1832 any more democratic.

One of the most strikingly resilient interpretations of county politics, put forward by the American sociologist D. C. Moore, has been the idea of ‘deference voting’. Vast numbers of newly enfranchised tenant farmers, Moore argued, overwhelmingly polled the same way as their landlords – willingly or otherwise – as part of ‘deference communities’, effectively bolstering the power of the aristocratic landed elite in Britain’s political system and the influence of traditional landed interests (see cartoon below). The tensions between agriculture and industry that underpinned so many 19th century political developments at Westminster, including of course the famous repeal of the corn laws in 1846, have often been linked back to this reconfiguration of British politics in 1832.

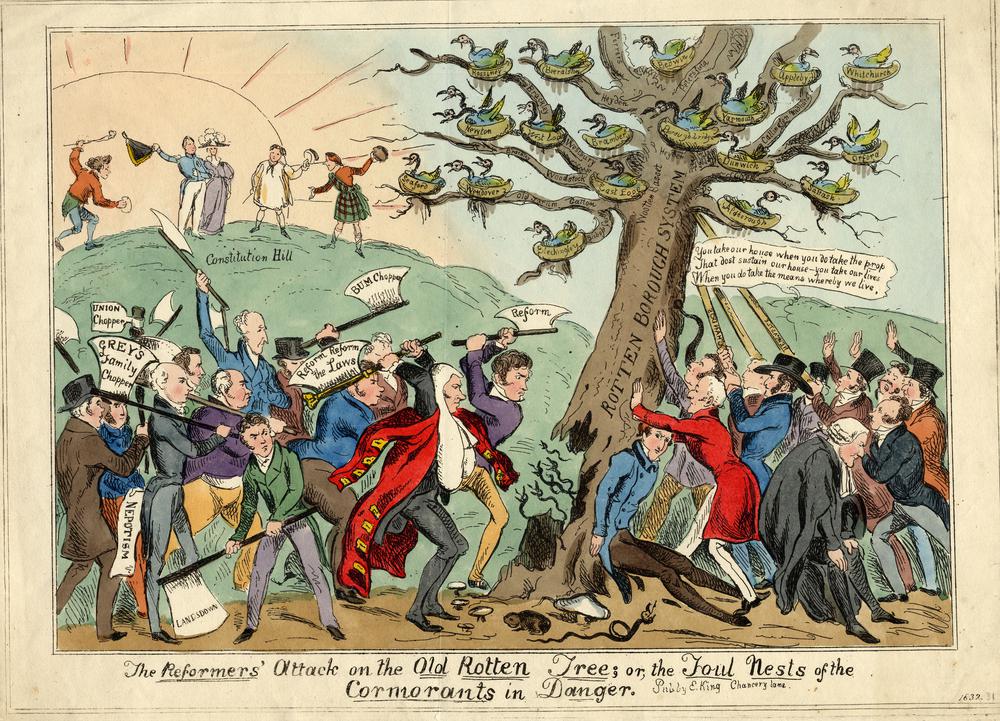

Another boost to the ‘county interest’, which is sometimes overlooked, resulted from the Reform Act’s redistribution clauses. As well abolishing the infamous ‘rotten’ boroughs and allocating new MPs to unrepresented towns and cities, almost the same number of extra MPs were given to the English counties. This was done by turning 26 existing county constituencies into 52 double member seats and allocating a third MP to seven counties. The impact on the House of Commons of increasing the number of English county MPs in this way, from 82 in 1831 to 144 in 1832, was arguably just as profound as the Act’s allocation of 63 new MPs to rapidly industrialising English towns, where most attention has traditionally been focussed.

New research by Dr Martin Spychal, published in his book Mapping the State: English Boundaries and the 1832 Reform Act, helps to show just how important this reconfiguration of ‘interests’ and the complex boundary changes of the 1832 Reform Act were in reshaping Britain’s political landscape after 1832. Other pioneering research, carried out by Dr James Smith, has explored the Act’s broader impact on the evolving relationship between the four different nations of the UK and on Parliament’s use of UK-wide legislation in the early Victorian era.

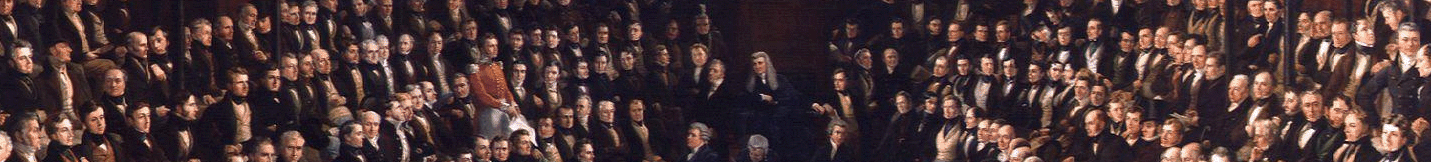

In our own ongoing research on MPs and constituency politics for the 1832-68 project, it has been the cultural impact of reform that has really stood out. The way MPs behaved and the way their constituents expected them to behave clearly shifted as a result of reform, with many MPs – particularly those elected as radicals – becoming far more active and accountable and publicising their activities in the press and through constituency meetings as never before. The growing ‘rage for speaking’ in debate, the introduction of a new press gallery, new public access (including a ladies’ gallery), new voting lobbies and the formal publishing of votes of MPs were just some of the ways in which parliamentary politics began to become more open and ‘representative’ after 1832, just as many anti-reformers had feared. All this, however, was complicated by the parallel survival of many older traditions, especially in the pre-reform constituencies. Here almost tribal patterns of non-party voting, the cult of ‘independent’ MPs, the survival of many ‘pocket’ boroughs and above all the widespread use of bribery, drink and corruption at election time all helped to limit the pace of change after 1832.

Ultimately it would take many other reforms to Britain’s representative system, including the abolition of public voting in 1872 with the introduction of the secret ballot to really bring about more fundamental change.

Further Reading:

‘The English reform legislation, 1831-32’, in The House of Commons, 1820-32, ed. D. Fisher (Cambridge University Press, 2009), i. 374-412 VIEW

‘Nineteenth-century electoral reform’, Modern History Review, xviii (2015), 8-12 VIEW

‘Electoral reform and the political modernization of England’, Parliaments, Estates, and Representation, xxiii (2003), 49-67 VIEW

This is an updated version of an article originally published on the Victorian Commons website on 7 June 2022, written by Dr Philip Salmon.