Concluding her series on the 1883 Corrupt Practices Act, Dr Kathryn Rix of our House of Commons, 1832-1945 project looks at the long-term consequences of this major reform.

In the wake of the corruption and expense of the 1880 general election, Sir Henry James, attorney general in Gladstone’s Liberal government, oversaw a landmark piece of legislation which aimed to clean up Britain’s elections: the 1883 Corrupt and Illegal Practices Prevention Act. When this measure was first introduced in 1881, The Times remarked that

if passed in its present form, it can scarcely fail to effect something like a revolution in the mode of conducting Parliamentary elections.

Although James accepted several amendments as the bill passed through the Commons, its core principles remained intact. It restricted how much candidates could spend at elections and what they could spend it on; increased the penalties for corrupt practices, including bribery and ‘treating’ voters with food and drink; and introduced the new category of illegal practices, which including illegal employment and illegal payment.

The first English contest under these new rules, the November 1883 York by-election, suggested that the Act would indeed transform the practice of electioneering. In keeping with its limits, York’s candidates spent just over a tenth of what the 1880 contest had cost, and the number of paid election workers and rooms hired for electioneering fell dramatically. However, some small-scale bribery and treating persisted.

The Third Reform Act of 1884-5 had made major changes to the electoral system by the time the first general election under the 1883 Act’s terms was held in 1885. The extension of the franchise meant that the electorate grew from 3,152,000 in 1883 to 5,708,000 in 1885, while the redistribution of seats into largely single member constituencies completely redrew the electoral map. This major overhaul of the electoral system – particularly the removal of small boroughs and the increased electorate – made its own contribution to diminishing corruption. The 1883 Act was, however, crucial in providing the framework within which candidates – increasingly with the assistance of professional agents overseeing local constituency associations – had to cultivate the votes of this mass electorate.

Election expenditure by candidates declined significantly following the 1883 reform. Candidates’ declared expenditure in 1885 was over £700,000 less than in 1880, despite a longer period of election campaigning and a far larger electorate. The average cost per vote polled fell by three-quarters, from 18s. 9d. to 4s. 5d., and never exceeded this in the period before the First World War, as the table below shows. Assisted by the Act’s restrictions, candidates did away with unnecessary expenditure on vast numbers of election workers or decorative items such as flags and banners.

| Election year | Total expenditure (£) | Average cost per vote polled |

| 1880 | 1,737,300 | 18s. 9d. |

| 1885 | 1,026,646 | 4s. 5d. |

| 1886 | 624,086 | 4s. |

| 1892 | 958,532 | 4s. 1d. |

| 1895 | 773,333 | 3s. 8¾d. |

| 1900 | 777,429 | 4s. 4d. |

| 1906 | 1,166,859 | 4s. 1¼d. |

| 1910 (Jan.) | 1,297,782 | 3s. 11d. |

| 1910 (Dec.) | 978,312 | 3s. 8d. |

Source: Kathryn Rix, ‘“The elimination of corrupt practices in British elections”? Reassessing the impact of the 1883 Corrupt Practices Act’, English Historical Review, cxxxiii (2008), 77

One of the problems revealed in 1880 had been that the total declared in candidates’ election accounts did not always reflect their true expenditure. The 1883 Act made a false declaration of expenses an illegal practice, which undoubtedly encouraged more accurate accounting. However, it remained the case that these official returns did not always present the full picture. One leading Liberal agent claimed in 1907 that

every agent has heard of cases where it has been necessary to “fake” the accounts in order to make it appear that no illegal expenditure has been allowed.

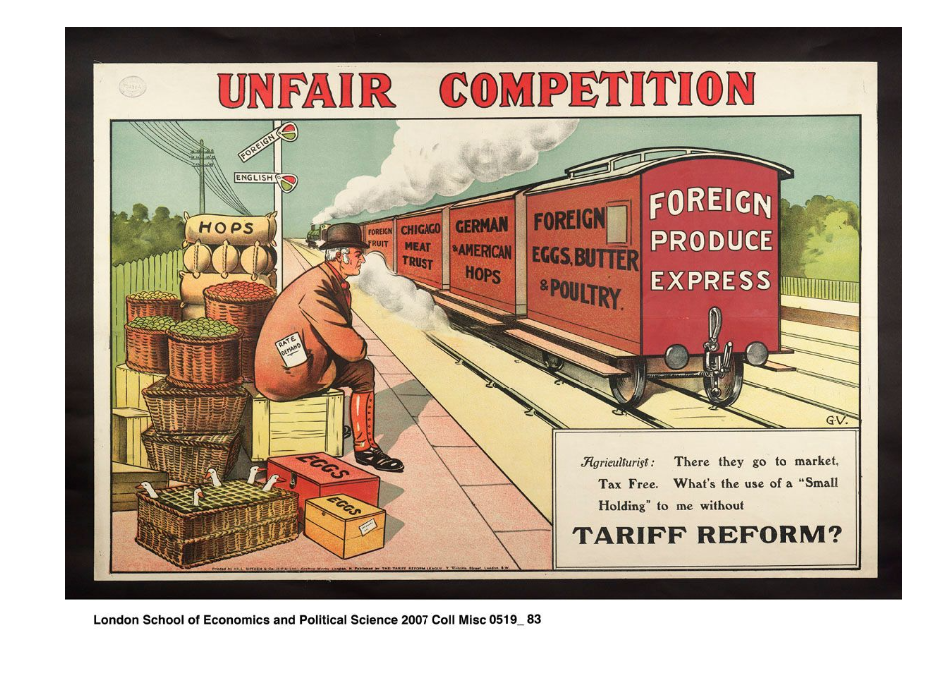

Such falsification of accounts broke the law, but there were also growing concerns about other expenditure which infringed the spirit, if not the letter, of the 1883 Act. Spending at elections by pressure groups such as the Tariff Reform League or temperance organisations – who held meetings, hired committee rooms and distributed leaflets and posters – might benefit particular candidates, but did not have to be included in their accounts.

At the 1892 election the Liberals were particularly concerned about the £100,000 allegedly spent by members of the drink trade in support of Conservative candidates, while in the early years of the twentieth century it was the greater spending power of the pro-Conservative Tariff Reform League in comparison with the pro-Liberal Free Trade Union which sparked most anxiety. The matter was raised in the Commons in February 1908 when 133 Liberal and Labour MPs (and one Liberal Unionist) backed an amendment regretting ‘the way in which large sums, derived from the secret funds of the Tariff Reform League and other similar societies, are spent in electoral contests without being returned in the candidates’ expenses’. A few months later the 1883 Act’s author Henry James corresponded with the lord chancellor about possible legislation to restrict such spending.

These were not the only ways in which the 1883 Act’s aim of curbing the electoral influence of wealth was apparently being evaded. James raised concerns about spending between elections by local party organisations and associated bodies such as the Primrose League on social activities and entertainments. This would have been classed as treating if undertaken in support of the candidate during the election. Yet James argued that

the corruption which causes a man to profess a political faith is as injurious as that which induces him to fulfil it by recording his vote.

In 1892 Conservative MPs at Hexham and Rochester were unseated by petitions because they had subsidised entertainments provided by the local Conservative association or Primrose League, raising hopes that such social activities might be curtailed. These were dashed by the 1895 Lancaster petition, which saw the Conservative MP retain his seat, despite the local party’s extensive programme of ‘politics and pleasure’, from dances to potato pie suppers. Crucially though, the MP had not subsidised these events.

Another continued source of spending to secure political influence was the ‘nursing’ of constituencies by candidates and MPs, who made charitable donations and subscribed to local clubs and institutions, in the hope of winning favour. The Conservative MP Frederick Milner complained in 1897 that

no pig, or cow, or horse dies in the constituency without the member being … asked to contribute towards another. He is expected to assist in the building or repair of each church and chapel … , to subscribe to all the cricket and football clubs, friendly societies, clubs, agricultural shows, and various worthy charities.

Some MPs spent hundreds of pounds annually in this way and the future Liberal prime minister Henry Campbell-Bannerman warned in 1901 that ‘the spending of money for the purposes of electoral influence’ was ‘one of the great dangers now affecting our political system’. It raised the spectre of wealthy ‘carpet-baggers’ effectively buying their way into seats where they had no local connections. It also had implications for the electoral chances of labour candidates, who could not afford such expenditure. However, suggestions that ‘nursing’ should be prohibited came up against the belief that, as MPs were often prominent local employers or landowners, philanthropy was a natural part of their social duties, irrespective of any political ambitions. Private members’ bills on the question in 1911 and 1912 failed to progress beyond their first reading.

The 1883 Act had clearly done much to curb election spending, but had not eradicated the electoral influence of wealth. A similar pattern emerges when assessing its impact on corruption. The number of MPs unseated by election petitions fell dramatically. Eighteen MPs lost their seats because of bribery and other corrupt practices at the 1880 election. In contrast, despite the law’s increased stringency, there was no election after 1885 which saw more than five MPs unseated. In total, 25 MPs were unseated for corrupt or illegal practices between 1885 and 1911. Cases such as the 1906 Worcester election petition, where around 500 individuals were involved in corruption, demonstrated that the 1883 Act had not been entirely successful.

Moreover, as with election accounts, the fall in petitions indicated a relative decline in corruption, but did not tell the full story. The significant costs and uncertain outcome of petitions deterred petitioners. So too did the unpopularity of petitions among voters, which might prove damaging to future election prospects. Petitioners also had to be sure that the election had been pure on their own side, or risk recriminatory charges. Where both parties had been involved with corruption, it might be better to collude to cover matters up, avoiding the potential threat of the constituency being disfranchised.

There continued to be rumours of corruption in constituencies which escaped petitions. The Liberal election agent for Thanet published a detailed account of the electoral misdeeds of Harry Marks, who won the seat for the Conservatives in 1906. He alleged that Marks had exceeded the 1883 Act’s limits, falsified his election accounts and funded treating and other forms of corruption. Marks had only narrowly survived an election petition against him in another constituency in 1895 and his involvement in commercial fraud was notorious. Thanet’s Liberals did not, however, petition against him, deterred by the expense and the difficulty of securing reliable witnesses who would not be ‘got at’ by Marks.

The complicity of both parties in corruption at Penryn and Falmouth, where it was alleged that ‘every man in the place was bought’, apparently prevented a petition after the 1900 election. Electoral malpractice continued: John Barker, Liberal MP from 1906 until his January 1910 defeat, later admitted to having spent thousands of pounds more than the Corrupt Practices Act’s limits during his two contests.

Yet while corrupt practices were not eliminated, The Times’s forecast of a revolution in electioneering remained accurate. Electoral contests after the 1883 Act were far purer and less costly than before this landmark reform. Sir Harry Verney, a veteran MP who first entered the Commons in 1832, and sat intermittently until 1885, summarised the transformation in 1892 when he reflected on

the great improvements I have lived to see in elections, when I remember the bribery, the drunkenness, and the extravagance of the old political contests.

Further reading:

C. O’Leary, The elimination of corrupt practices in British elections, 1868-1911 (1962)

Kathryn Rix, ‘“The elimination of corrupt practices in British elections”? Reassessing the impact of the 1883 Corrupt Practices Act’, English Historical Review, cxxxiii (2008), 65-97

C. R. Buxton, Electioneering Up-To-Date, With Some Suggestions for Amending the Corrupt Practices Act (1906)

For the first two articles in this series, see here and here.