In this blog, Dr Alex Beeton reviews a fascinating colloquium, held recently at the History of Parliament’s office in Bloomsbury Square.

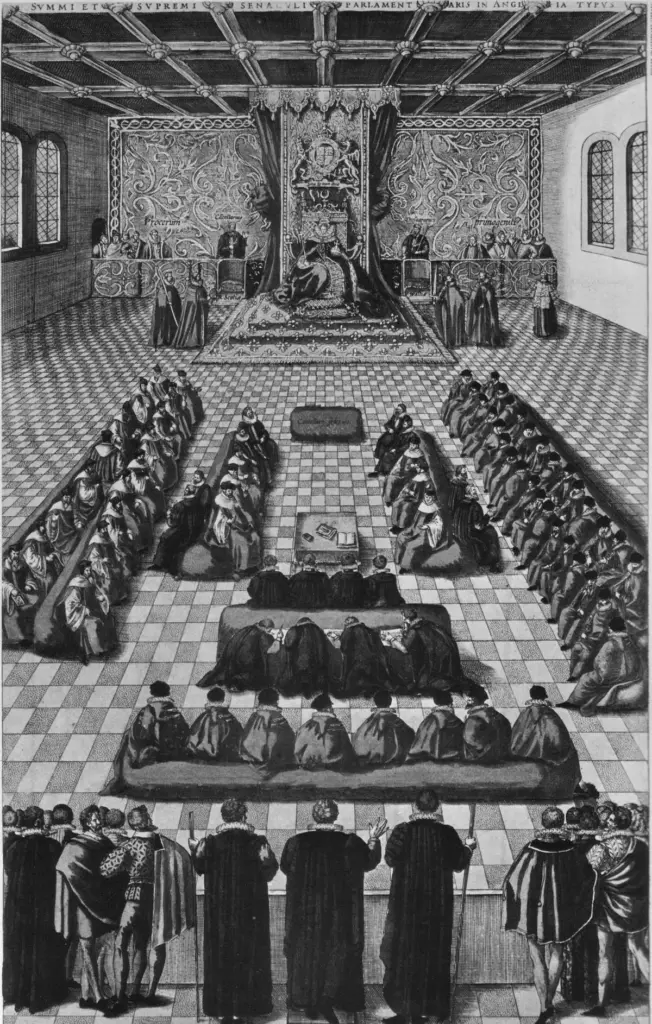

In the early modern period, both England’s Church and its Parliament changed. A Catholic country split from Rome and the importance and prominence of the two Houses of Parliament dramatically increased. These two seismic shifts were not isolated from one another. Parliament’s role in the transformation and governance of England’s ecclesiastical settlement has been much debated, especially since the seminal work of Sir Geoffrey Elton, who argued Parliament’s role in enacting the early stages of the Reformation was a formative moment in parliamentary history. To address this complex relationship, the History of Parliament hosted a colloquium on 26 April 2025 entitled ‘Parliament and the Church, c.1530-c.1630’. Convened by Dr Alexandra Gajda (University of Oxford) and Dr Alex Beeton (History of Parliament), eight speakers and almost twenty audience members, many of them leading academics, debated a myriad of issues and topics in an energising and convivial atmosphere.

The eight speakers, split between three chronological panels, had produced their papers, (which will be published in a special edition of Parliamentary History) for pre-circulation; this meant the majority of the day was spent in discussion of their findings. In the first panel, Dr Gajda and Dr Paul Cavill (University of Cambridge) delved into the first half of the sixteenth century. Dr Cavill launched a vigorous attack on a famous essay of Elton’s, ‘Lex Terrae Victrix: the triumph of parliamentary law in the sixteenth century’ which argued that in the 1530s emerged the twin ideas of the supremacy of parliamentary law (i.e. common law) and the notion of the king-in-Parliament being the ultimate authority in the kingdom. Using the example of the court of delegates, Dr Cavill’s paper skilfully showed how laws other than common law continued to be used, and that the monarchy ruled through the common law rather than under it. Dr Gajda took the discussion forward into the mid-century, showing that the Parliaments of Edward VI deserve to be known as Reformation Parliaments which enacted sweeping reforms via statute. This process did not occur because the crown believed the two Houses to be particularly appropriate as authorities on religious matters, but because parliamentary statute reached all the monarchy’s subjects and because the lay members of Parliament were more amenable to changes in religious practices than Convocation.

After a lunch break, the second panel of the day focussed largely on the reign of Elizabeth I. Dr Paul Hunneyball (History of Parliament) produced an excellent study of the bishops in the Lords as a group during the 1584-5 Parliament. Drawing on the cutting-edge research of the Lords 1558-1603 project, Dr Hunneyball teased out a number of insights about the bishops and their political activities, showing the value of investigating the Lords Spiritual as a body. Dr Esther Counsell’s (Western Sydney University) fascinating contribution focussed on the same Parliament, investigating a manuscript speech-treatise written by Robert Beale, clerk of the privy council, which was intended for the Parliament but never delivered. Dr Counsell argued that Beale was representative of a group within the English establishment which was eager for further religious reformation, worried about the encroachment of Catholicism, opposed to the jurisdictional overreach of ecclesiastical authorities and courts, and concerned that the denial of Parliament’s authority to determine ecclesiastical matters would undermine the stability of Elizabeth’s reign. The third speaker, Adam Forsyth (University of Cambridge), took the panel into the early seventeenth century with an impressive analysis of statutory interpretation and multilateralism in judicature, delineating the disputes between civil and common lawyers about who could interpret statutes and the different positions which civil lawyers adopted concerning the prerogatives of statutory interpretation.

Despite the hot weather and the lack of air conditioning in the History of Parliament’s common room, spirits and energy remained high for the third and final panel of the day. Professor Kenneth Fincham (University of Kent), who was chairing, prefaced the panel with an elegantly concise set of remarks about Parliament and religion in the 1630s before introducing the speakers. Emma Hartley’s (University of Sheffield) paper insightfully investigated the early Jacobean Parliaments, showing how their disputes and proceedings demonstrated that the future of the English Church was still considered to be uncertain at the time. Enormous tensions existed over ecclesiastical jurisdiction, Parliament’s role in religious matters, and the constitutional positions and authority of bishops and Convocation. She was followed by Dr Kathryn Marshalek (Vanderbilt University) whose paper offered a brilliant account of how, pace earlier revisionist historiography, religious issues and constitutional crisis became a deadly combination in English politics well before the end of the 1620s. Dr Marshalek’s study of the 1620s Parliaments argued that the European geo-political situation made a re-negotiation of the English religious settlement, and the place of English Catholics within it, possible. It was in this context that calls from Parliament for the enforcement of religious conformity became more forceful and provoked a broader consideration of the relationship between the king, royal prerogative, and parliamentary statute. Closing the day’s proceedings, Dr Andrew Thrush (History of Parliament) offered a thought-provoking overview of the right of the House of Commons to debate religious matters between 1566-1629. He discussed why the Commons right to do so was not clearcut and why the crown, despite strenuous efforts, repeatedly failed to prevent the lower House from considering religious matters. He finished by concluding that the Commons achieved little in the way of tangible results through their extensive debates since they lacked the ability to enforce their will.

As with their predecessors, this final panel stimulated plenty of questions and debate between speakers and audience which continued in a more relaxed atmosphere following the end of official proceedings. As the vivacity of the day demonstrated, the relationship between Parliament and Church in early modern England remains a topic with potential for important discoveries and exciting insights.

ALB