In this guest article, Dr Caroline Shenton, author of ‘The Day Parliament Burned Down‘ and ‘Mr Barry’s War: Rebuilding the Houses of Parliament after the Great Fire of 1834‘, describes the dramatic events that took place at the Palace of Westminster on 16 October 1834.

By the late Georgian period, the buildings of the Palace of Westminster had become an accident waiting to happen. The rambling complex of medieval and early modern apartments making up the Houses of Parliament – which over the centuries architects including Sir Christopher Wren, James Wyatt and Sir John Soane had attempted to improve and expand – was by then largely unfit for purpose. Complaints from MPs about the state of their accommodation had been rumbling on since the 1790s, and reached a peak when they found themselves packed into the hot, airless and cramped Commons chamber during the passage of the 1832 Reform Act.

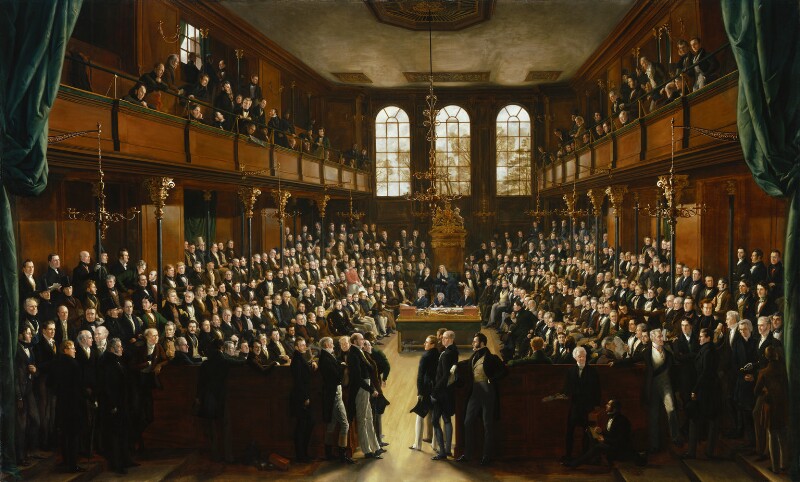

© National Portrait Gallery, CC BY-NC-ND 3.0. Hayter’s painting depicts the pre-fire House of Commons chamber, although he did not complete it until several years later.

Unable to agree on a solution for new accommodation, in the end the decision was made for them. The long-overdue catastrophe finally occurred on 16 October 1834. Throughout the day, a chimney fire had smouldered under the floor of the House of Lords chamber, caused by the unsupervised and ill-advised burning of two large cartloads of wooden tally sticks (a form of medieval tax receipt created by the Exchequer, a government office based at Westminster) in the heating furnaces below. Warning signs were persistently ignored by the senile Housekeeper and careless Clerk of Works, leading the Prime Minister Viscount Melbourne later to declare the disaster ‘one of the greatest instances of stupidity upon record’.

At a few minutes after six in the evening, a doorkeeper’s wife returning from an errand finally spotted the flames licking the scarlet curtains around Black Rod’s Box in the Lords chamber where they were emerging through the floor from the collapsed furnace flues. There was panic within the Palace but initially no-one seems to have raised the alarm outside, perhaps imagining that the fire – which had now taken hold and was visible on the roof – could be brought under control quickly. They were mistaken. A huge fireball exploded out of the building at around 6.30 p.m., lighting up the evening sky over London and immediately attracting hundreds of thousands of people.

The fire turned into the most significant blaze in the city between 1666 and the Blitz, burning fiercely for the rest of the night. It was fought by parish and insurance company fire engines, and the private London Fire Engine Establishment, led by Superintendent James Braidwood, the grandfather of modern firefighting theory. Hundreds of volunteers, from the King’s sons and Cabinet ministers downwards, manned the pumps on the night, and were paid in beer for their efforts. Contrary to popular opinion, onlookers in the vast crowds did not generally stand around cheering. Most were awestruck and terrified by the spectacle, and some suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder as a result. Others were injured in the crush, and plenty were pickpocketed, but astonishingly no-one died in the disaster.

As it burned, the fire stripped away the later, and often ugly, accretions of many centuries, revealing the beautiful gothic buildings beneath, including the Painted Chamber, St Stephen’s Chapel and its lower chapel of St Mary’s, in use at the time of the fire as the Court of Claims, House of Commons and Speaker’s Dining Room respectively. In the aftermath of the fire these became a focus for much antiquarian activity and delighted the sightseers touring the ruins.

By the middle of the evening it was clear that the fire was uncontrollable in most of the Palace. Westminster Hall then became the focus for Braidwood’s efforts and those of his men and hundreds of volunteers. The thick stone Norman walls provided an excellent barrier against the spread of fire, but the late fourteenth-century oak roof timbers were in great peril. ‘Damn the House of Commons, let it blaze away!’ cried the Chancellor of the Exchequer Viscount Althorp desperately, ‘But save, O save the Hall!’ The efforts of all, from the highest to the lowest, plus a lucky change of wind direction at midnight, and the arrival of the London Fire Engine Establishment’s great, floating, barge-mounted fire engine, finally started to quell the fire in the early hours and ultimately saved Westminster Hall. The fire crews finally left five days later, having put out the last of the fires which kept bursting out from the ruins.

The following day revealed a shattered and smoking collection of buildings, most of which were cleared in the months that followed and the stone sold to salvage merchants or pushed into the river. Temporary chambers and committee rooms were available for occupation by February 1835, and a government competition commenced to design a new Houses of Parliament on the ruined site. Charles Barry, aided by Augustus Pugin, won the commission and together they created the most famous building in the United Kingdom. The patched-up parts of the old Palace were finally pulled down in the early 1850s. Only Westminster Hall, the Undercroft Chapel of St Mary and part of the Cloister remain today of the survivors of 1834. The damage to the wrecked and uninsured Palace was estimated at £2 million. No-one, however was prosecuted, though the public inquiry which followed found various people guilty of negligence and foolishness.

Coming at a moment in British history between the Georgian and Victorian ages, the stagecoach and the railway, the demise of the medieval city of London and the birth of the modern one, it is easy to load the great fire of 1834 with a wider historical significance. Later commentators have seen it as symbolic of the constitutional changes brought about by the Great Reform Act of 1832, but at the time people were more likely to have seen it as a judgement from God for the passing of the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834, against which Charles Dickens – a parliamentary reporter at the time of the fire – railed in Oliver Twist.

This piece is a revised version of the article ‘The Fire of 1834’ by Dr Caroline Shenton, author of ‘The Day Parliament Burned Down‘, originally posted on historyofparliamentonline.org.