The death of Charles James Fox on 13 September 1806, just over eight months after that of his long-term rival, William Pitt the Younger, robbed British politics of a titan who had dominated affairs since the 1780s. And yet, in spite of being the talented heir to a parliamentary dynasty, Fox spent only a few months in office, and much of the latter part of his career was spent in opposition at the head of a ‘rump’ of loyal associates dedicated to reform about which Fox himself was decidedly uncertain.

Charles James Fox (1749-1806) was the second and favourite son of Henry Fox, 1st Baron Holland, who spoiled him as a child and secured his return to the Commons for Midhurst at the age of 19. A gambler and spendthrift, he held junior offices in Lord North’s ministry, but was dismissed from the treasury board for non-attendance and ill discipline in the House in February 1774. He inherited his father’s personal hostility towards George III, which was fully reciprocated, and by 1775 was the acknowledged leader of the opposition in the Commons (where he shone brilliantly in debate), friendly with Edmund Burke and the Rockingham Whigs, and adored by a coterie of personal friends among the independent Members, who were attracted by his charm and parliamentary talents. By identifying himself with the programme of the association movement he made his mark on the national stage, and in 1780 was returned free of expense for Westminster, the most prestigious constituency in the country.

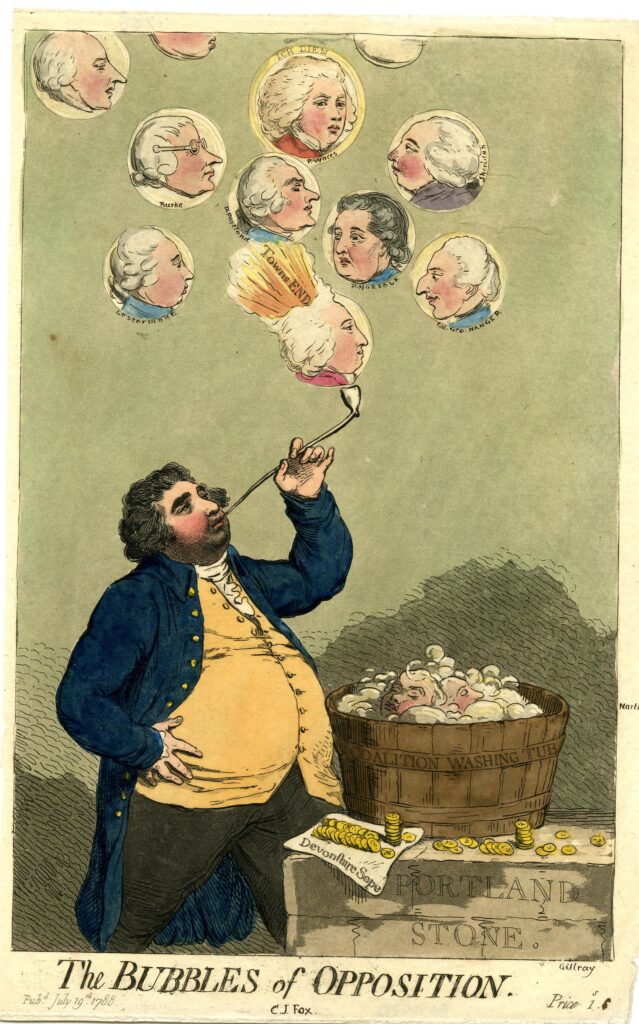

He was foreign secretary and leader of the Commons in Lord Rockingham’s administration of March 1782, but when the king chose his rival Lord Shelburne as premier on Rockingham’s death in July Fox resigned. He made an unprincipled coalition with North to overthrow Shelburne, which was achieved on the peace preliminaries, and in the subsequent coalition ministry, which the king was forced to accept in April 1783 after failing to find an alternative, was, as foreign secretary and leader of the Commons, the dominant figure, although the Whig 3rd duke of Portland was the figurehead premier. When George III seized the opportunity presented by Fox’s controversial and badly timed India bill to plot the downfall of the ministry and install William Pitt as prime minister in December 1783, Fox, who at the general election of 1784 was hard pressed in Westminster and only retained the seat after a prolonged scrutiny, found himself again in opposition, where he remained for all but the last eight months of his life. His hopes of a return to office in 1788 when his friend and roistering companion the prince of Wales seemed about to become regent were dashed by George III’s recovery from his insanity.

Fox, who had matured as a politician by 1789, welcomed the French revolution, but as events turned ever more violent and the threat to the European monarchies became more menacing his stance appalled the alarmist Burke, who publicly severed relations with him in May 1791. Fox was privately uneasy over the establishment by his friends Richard Sheridan and Charles Grey of the Society of the Friends of the People, intended to promote the cause of parliamentary reform, in April 1792, but he did not intervene to restrain them. While Portland, the overall leader of the opposition, was an alarmist on France, his extreme reluctance to destroy the Whig party prevented him from immediately parting company with Fox.

Fox secured a minority of 50, reportedly made up of 21 reformers, four men attached to Lord Lansdowne (as Shelburne had become) and some two dozen personal followers of his own, for his amendment to the address, 13 Dec. 1792, when he denounced Pitt’s policy as alarmist and subversive of constitutional liberties. His calls for peace negotiations with France, 14 and 15 Dec., were negatived without a division. The formation of Windham’s ‘third party’ and the conservative Whigs’ secession from the Whig Club in February 1793, when war with France broke out, brought the split in the party into heightened relief. The Portland Whigs ceased to act with the Foxites in opposition to the war, and in 22 divisions between 18 Feb. 1793 and 30 May 1794 for which minority lists have been found, the highest opposition muster was that of 59 for the amendment to the address, 21 Jan. 1794. A motion for peace negotiations, 30 May 1794, secured 55 votes. These figures contrast strikingly with the minorities of 172 and 116 for motions condemning Pitt’s warlike stance against Russia, 12 Apr. 1791 and 1 Mar. 1792. Portland broke with Fox in January 1794 and coalesced with the government seven months later.

About 55 Members (including Fox himself) can be identified as acting with the Foxite rump from late 1792. The most assiduous voters were Grey, Michael Angelo Taylor, Joseph Burch, Samuel Whitbread, Philip Francis, Sheridan, Lord Robert Spencer, William Smith, Dudley North, Lord William Russell, John Courtenay, Henry Howard, Richard Fitzpatrick, Banastre Tarleton and William Hussey. Beside the hard core of Foxites, a few Members cast occasional minority votes. Many of the 55 were gamblers and socialites, products of Eton or Westminster schools and personal friends of Fox. Almost half of them were directly or closely connected to the aristocracy, and many belonged to the interrelated families of the ‘grand Whiggery’. More than half sat for constituencies with fewer than 200 electors, while one third sat on the borough interest of an aristocratic patron. For all this, they included several men of considerable intelligence and talent, who, sharing Fox’s detestation of the royal prerogative, campaigned against the war and for reform in a bid to prevent what they saw as further curtailment of the liberties of the British people.

When the independent Members for Yorkshire, William Wilberforce and Henry Duncombe, moved an amendment to the address calling for peace negotiations, 30 Dec. 1794, the minority in favour rose to 73 (against 246). Subsequent motions on the same subject, 26 Jan. and 27 May 1795, secured 86 votes. While most of the new opposition voters on this issue were independent country gentlemen, some Whigs who had ceased to act with Fox on the outbreak of war returned to the fold. The modestly increased muster of Foxites between December 1794 and the dissolution in 1796 brought the reliable hard core to about 65.

This is a revised version of the article ‘The Foxite Whig Rump’ by David R. Fisher, originally posted on historyofparliamentonline.org.