Ahead of next Tuesday’s Parliaments, Politics and People seminar, we hear from Dr Caitlin Kitchener. On 28 January Caitlin will discuss the production, use and curation of radical material culture in the early nineteenth century.

The seminar takes place on 28 January 2025, between 5:30 and 6.30 p.m. It will be hosted online via Zoom. Details of how to join the discussion are available here.

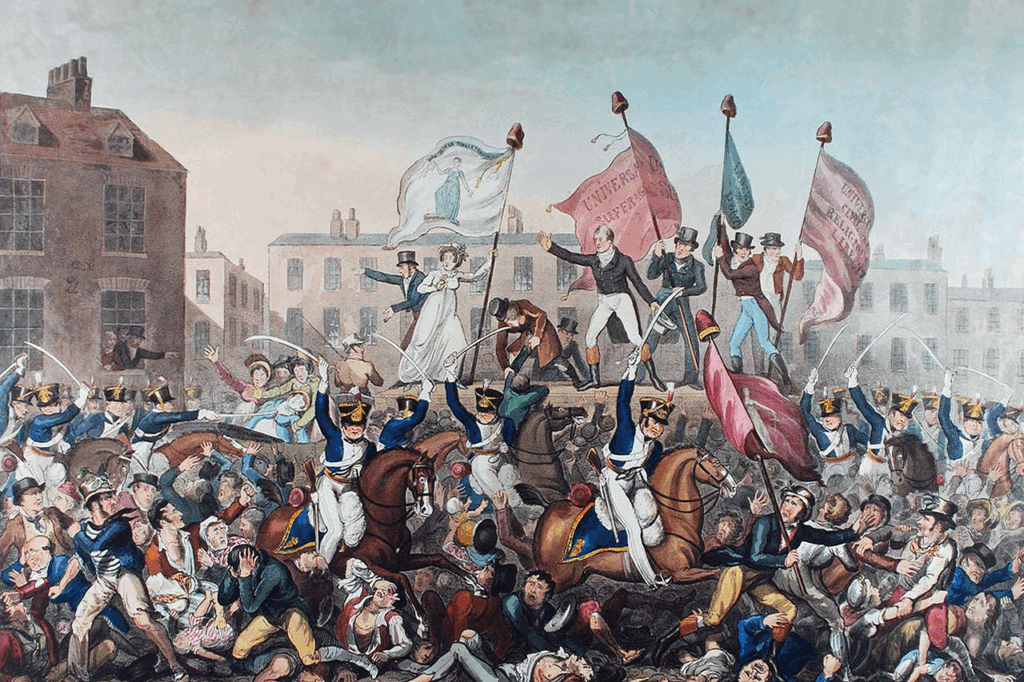

As numerous processions made their way to St Peter’s Field, Manchester on the 16th August 1819, many of the delegations carried banners and flags. Some had liberty caps. Others wore their Sunday best. Female reformers helped to make it a vibrant occasion, with female reform societies from Oldham, Royton, Stockport and elsewhere carrying specially made banners. Materiality was a crucial part of the radical performance.

Discussions about clothing, banners and liberty caps would have been occurring in the build up to what was meant to be a powerful declaration of the people’s desire for parliamentary reform as well as an opportunity to hear the famed orator Henry Hunt speak. However, the onlooking magistrates and yeomanry may have looked at the objects as being dangerous and seditious.

The banners in combination with marching or processing may well have influenced the magistrates’ decision to disperse the crowd with force. The walking sticks carried by some of the crowd (who were travelling some distance on foot to attend) were transformed into weapons, justifying to the magistrates the actions of what would become Peterloo.

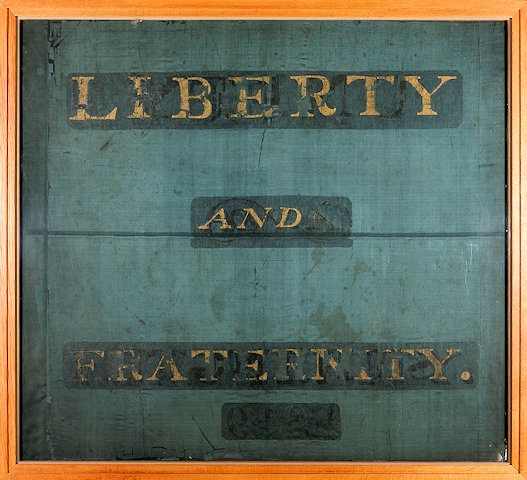

During the violent turmoil when the yeomanry aggressively dispersed the crowd, it was not only people who were attacked. Samuel Bamford recorded in his autobiography that ‘Thomas Redford, who carried the green banner, held it aloft, until the staff was cut in his hand, and his shoulder was divided by the sabre of one of the Manchester yeomanry’. At least one banner made it out of Peterloo unscathed and is a rare survival. The Middleton banner, painted ‘Unity and Strength 1819’ on one side and ‘Liberty and Fraternity’ on the other, provides a tantalising insight into what these banners would have looked like. These are contested and evocative objects.

The importance of radical and reform material culture in the early nineteenth century is evident on account of its frequent use in mass meetings. The role of such objects in group and community identity construction has also been recognised. However, what is less well known is how these objects were being made, who was making them, and where they were stored. This was an era prior to the professionalisation of banner making in the late 1800s, with George Tutill being particularly well-studied. The who, where, and why of the production of radical and reform material culture needs to be understood as it is intimately connected to identity construction.

Within archaeology, researchers are interested in ‘object biographies’ – the life cycle of an artefact. This means that production/creation, use, curation, and death/destruction/deposition of an object all need to be investigated. The context the object is created and used in is also an important element. Was a sign maker commissioned to paint the banner? Did women stitch and sew liberty caps at home? Who got to carry the banner poles into the meeting? Where was the banner kept following the meeting? These questions have – at times – rather elusive answers. However, even asking them and probing possibilities can help us to consider the domestic, communal and radical spaces and identities of early nineteenth-century parliamentary reform.

The transcript of Henry Hunt’s trial at York provides some fascinating insights into how radical material culture was being made. Robert Harrop, a spinner from Lees, Manchester, was called as a witness. Harrop stated that some bleached cambric was bought to make a flag for the meeting but when the inscriptions were painted on in black, they showed through the other side. For the sake of having a better banner, they agreed to make it black with white lettering as these were the only paints they had. Various people contributed inscriptions to the banner (Harrop chose “Unite and Be Free”) and some unnamed women added the fringe.

In a similar occurrence, William Binns made a fleur-de-lis ornament for the top of the banner pole and was instructed to paint it yellow, but used red as that was the only colour available to him. These witness statements allude to a community-based approach but also a practical outlook. What is not recorded is where these objects were made.

But there is another part to an object biography too; how is the object remembered? Objects can be revived post-death or deposition. There is a low surviving rate of material culture related to early nineteenth-century radicalism and parliamentary reform. No banners are known to have survived from the era of English and Welsh Chartism.

Some of this will be due to the materiality of these objects; textiles can suffer if not kept in suitable environmental conditions. Thus, we need to think about how these objects were stored, perhaps forgotten or lost, and remembered through people reminiscing and recollecting. Memory can include more authorised forms of heritage, such as the display of banners at the People’s History Museum, to local and community groups engaging with political heritage, including the Peterloo Memorial Campaign’s recreation of the Saddleworth banner present at Peterloo.

While there are more questions than answers at the moment, the framework of object biography encourages us to think about the different life stages of the material culture of radicalism. Preliminary work is currently pointing towards identity construction, memory and heritage as all being important themes in why objects were made but also, perhaps, as to why many of these objects do not survive.

CK

The seminar takes place on 28 January 2025, between 5:30 and 6.30 p.m. It is will be hosted online via Zoom. Details of how to join the discussion are available here.