Ahead of next Tuesday’s Parliaments, Politics and People seminar, we hear from Dr Ellen Paterson, Keble College, University of Oxford. On 11 March Ellen will discuss petitioning and parliamentary memory in the Long Parliament (1640-1642).

The seminar takes place on 11 March 2025, between 5:30 and 6.30 p.m. It is fully ‘hybrid’, which means you can attend either in-person in London at the IHR, or online via Zoom. Details of how to join the discussion are available here.

In the opening years of the Long Parliament, subjects from across the realm eagerly embraced the opportunity to petition both the Commons and the Lords. After eleven years without a Parliament, during the period known as Charles’s ‘personal rule’, and following the abrupt Short Parliament in April-May 1640, petitioners sought to channel their complaints to a new body of authority which they hoped would prove more receptive to their complaints than had the King and Privy Council.

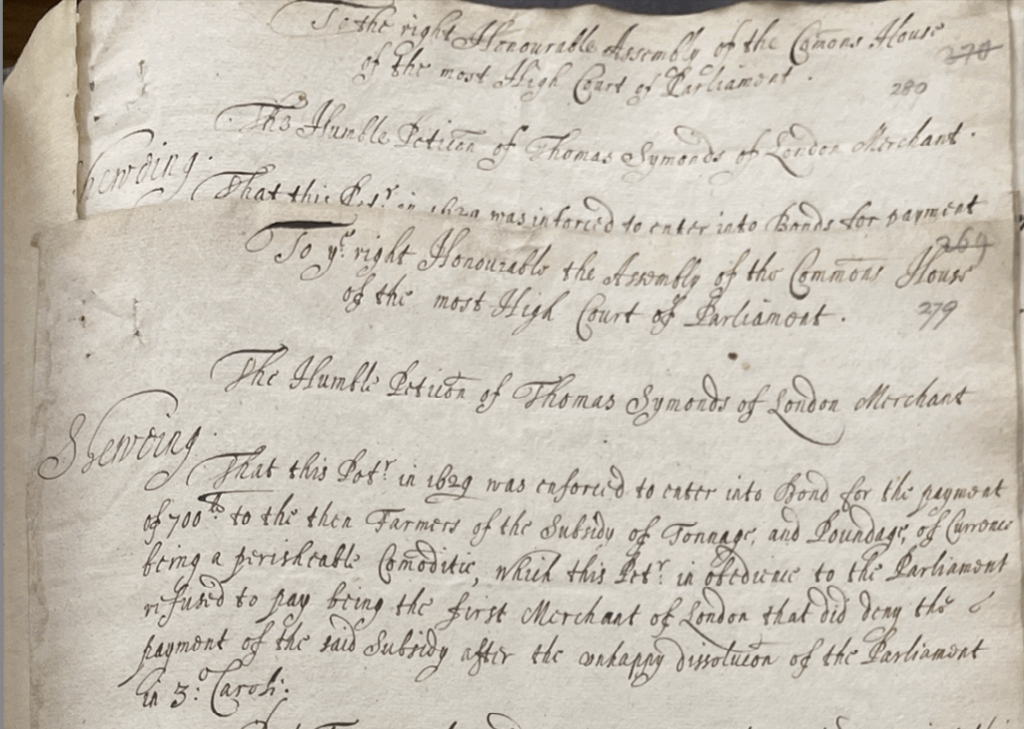

One such petitioner was the Levant Company merchant Thomas Symonds. Penning his suit in 1641, Symonds informed the Commons of his refusal to pay customs duties on currants and the subsequent imprisonment he had faced at the hands of Charles’s custom farmers. He appealed to the Commons to consider the costs and damages he had incurred, including £40 to the farmers and £100 defending himself at law, as he sought compensation for his troubles. Like so many other petitioners approaching the Long Parliament, Symonds sought redress for grievances which had occurred in the 1630s.

However, Symonds went further than lamenting his own personal troubles. To appeal to the Commons, he also invoked the memory of events which had transpired in the Parliament of 1628-1629. Then, Charles’s use of a range of unpopular fiscal measures, including monopolies, impositions, and tonnage and poundage had been thoroughly investigated. The latter was particularly contentious as, despite Parliament usually granting the monarch the right to collect this custom duty for life, MPs in Charles’s first Parliament had only granted this for a year.

Charles’s continued collection of tonnage and poundage throughout his reign was therefore perceived as illegal. In a remonstrance presented by MPs to the King in 1628, they had articulated their concern that this was a form of taxation without consent. And amongst the raucous proceedings which saw MPs forcibly keep the speaker in the chair to avoid adjournment on 2 March 1629, the MP Sir John Eliot also attempted to have read a declaration which included tonnage and poundage as a key grievance in the realm. Any merchants who paid it, he had claimed, were traitors to the realm.

Over ten years later, Symonds referred to these events in his petition to the Commons. He made the rather bold claim that, ‘in obedience to the Parliament’, he had been the ‘first merchant of London that did deny the payment of the said subsidy after the unhappy dissolution of the Parliament’. His refusal to pay customs on currants was therefore presented as driven by Parliament’s direct commandment. He therefore moved to depict himself as a staunch protector of both ‘the public right of the subject and of himself’, protesting a duty which was harmful to the liberties of subjects throughout the realm.

Symonds’s petition illustrates two important themes which will be the focus of this paper. Firstly, the prevalence of petitioners approaching what they termed as a ‘great court of justice’, many of whom were driven to approach both the Commons and Lords by their economic concerns. Secondly, it reveals the important ways through which memory was tactically utilised by petitioners. Despite years between parliamentary sittings, petitioners proved able and willing to draw on the actions of preceding sessions, maintaining lines of continuity between different Parliaments and, in the process, contributing to the fostering of Parliament’s institutional memory.

In pre-existing historiography, the opening years of the Long Parliament are often analysed in terms of high politics, as a crucial period of escalating tensions which would lead to the outbreak of conflict in 1642. Yet for many subjects approaching it in these years, Parliament was not necessarily seen as a staging post to the Civil War, but as an institution with the time and inclination to offer redress. Many subjects looked backwards, not forwards, as they framed their requests.

Scholars have spent much time examining the large-scale petitions presented by subjects from across the realm, calling for root and branch reform or combining their concerns with the decay of trade with reflections on the rise of popery. Comparatively less attention has been paid to the plethora of manuscript petitions surviving in the papers of individuals MPs and in the Parliamentary Archives. An important exception has been the work of James Hart, which revealed the rise in the number of petitioners approaching the Lords with private suits and petitions. Indeed, such was the volume of petitions presented that both the Lords and the Commons periodically issued orders calling for the cessation of any new petitions, as they cleared this backlog.

A closer analysis of the rhetoric and argumentative strategies deployed by petitioners seeking relief for economic grievances sheds light on the importance of memory for supplicants approaching this Parliament. Petitioners’ interactions with past parliaments, including those of the Jacobean period (1603-1625), influenced which House they decided to approach, whilst others harkened back to decisions made in sessions in 1621 and 1624 as they sought to appeal to MPs.

As this paper will show, this was especially true for the realm’s glassmakers, who sought to challenge a patent of monopoly held by the courtier Sir Robert Mansell. Their success in securing parliamentary condemnations of his monopoly in 1614 and 1621 shaped their complaints and emboldened them to direct their complaints to the Commons in 1641-42.

Not all petitioners were necessarily truthful in their presentation of past parliamentary proceedings. One of the realm’s most important regulated companies, the Merchant Adventurers, manipulated the memory of actions against them in 1624 as they sought to persuade MPs that they had always been staunch protectors of their corporate regulation of trade.

Memory could be manipulated and selectively deployed by petitioners, as yet another tool in an already sophisticated armoury of petitioning tactics. This occurred at the same time as Parliament’s own record-keeping practices were evolving and developing, and its institutional memory was being forged.

By exploring the ways through which petitioners looked back to past parliamentary decisions, subjects’ contributions to this process will be revealed. It was not just sitting members or record-keepers who helped to create memory. Through their actions, it becomes clear that Parliament was perceived not as an event, but as an institution.

EP

Ellen’s seminar takes place on 11 March 2025, between 5:30 and 6.30 p.m. It is fully ‘hybrid’, which means you can attend either in-person in London at the IHR, or online via Zoom. Details of how to join the discussion are available here.

Further reading:

J. S. Hart, Justice upon Petition: The House of Lords and the reformation of justice 1621-1675 (London, 1991)

P. Seaward, ‘Institutional Memory and Contemporary History in the House of Commons, 1547-1640’, in P. Cavill and A. Gajda (eds.), Writing the History of Parliament in Tudor and early Stuart England (Manchester, 2018), pp. 211-28.

J. Peacey and B. Waddell (eds.), The Power of Petitioning in early modern Britain (London, 2024)

J. Peacey, Print and Public Politics in the English Revolution (Cambridge, 2013).

C. Russell, Parliaments and English Politics 1621-1629 (Oxford, 1979)

S. K. Roberts (ed.), The House of Commons 1640-1660 (9 vols, Suffolk, 2023).