In his last post for the Georgian Lords, From bills to bullets: Spring 1775 and the approach to war in America, on the advent of the American War of Independence, Dr Charles Littleton left things hanging with the prorogation on 26 May 1775. Now, he continues the story into the autumn with the declaration of war and a key government reshuffle.

Following the prorogation of Parliament at the end of Mary 1775, the situation changed for the worse, as news of the armed confrontation at Lexington and Concord in April reached Britain. Following that, reports of Britain’s bloody pyrrhic victory in June at Bunker Hill (Charlestown) arrived in London on 25 July. Almost immediately the government of Lord North decided on sterner measures against the unruly colonists. The principal minister co-ordinating the deployment of troops was North’s step-brother, William Legge, 2nd earl of Dartmouth, secretary of state for America. The office had only existed since 1768 and Dartmouth, who came from a family that had long contributed officials, had held it since August 1772.

Dartmouth’s papers suggest that he was efficient in preparing for an increased military presence in America. As someone who had always sought conciliation, more troublesome to him were plans for a Royal Proclamation declaring the American colonies ‘in rebellion’ and thus that a state of war existed between Britain and America. On 1 February 1775, he had refused ‘to pronounce any certain opinion’ regarding the earl of Chatham’s conciliation bill, and even admitted he ‘had no objection to the bill being received’. [Almon, Parl. Reg., ii. 23] Similarly, in August, Dartmouth had feared that a formal declaration of war would jeopardize negotiations. He held off on agreeing to the Proclamation for as long as he could on the news that the Continental Congress was sending new proposals for a settlement: the so-called ‘Olive Branch Petition’. By late summer, however, the government was in belligerent mood, and on 23 August the Proclamation of Rebellion was promulgated.

Thus, when Parliament resumed on 26 October, Britain and the colonies were formally at war. Even Lord North ‘had changed his pacific language and was now for vigorous measures’. [H. Walpole, Last Journals, i. 490] One result was a ministerial reshuffle over 9-10 November. This gave the government a radically new complexion, and Dartmouth was moved from the American office, apparently unwillingly.

To soften the blow, the king offered Dartmouth his choice of being appointed groom of the stole, secretary of state for the southern department, or taking a pension. Dartmouth turned them all down and instead insisted on taking over as lord privy seal. The king had intended the place for Thomas Thynne, 3rd Viscount Weymouth, but made him secretary of state for the southern province instead. Dartmouth, George III complained, was not ‘in the least accommodating’ by ‘carrying obstinacy greatly too far’. [Fortescue, iii. 282-88]

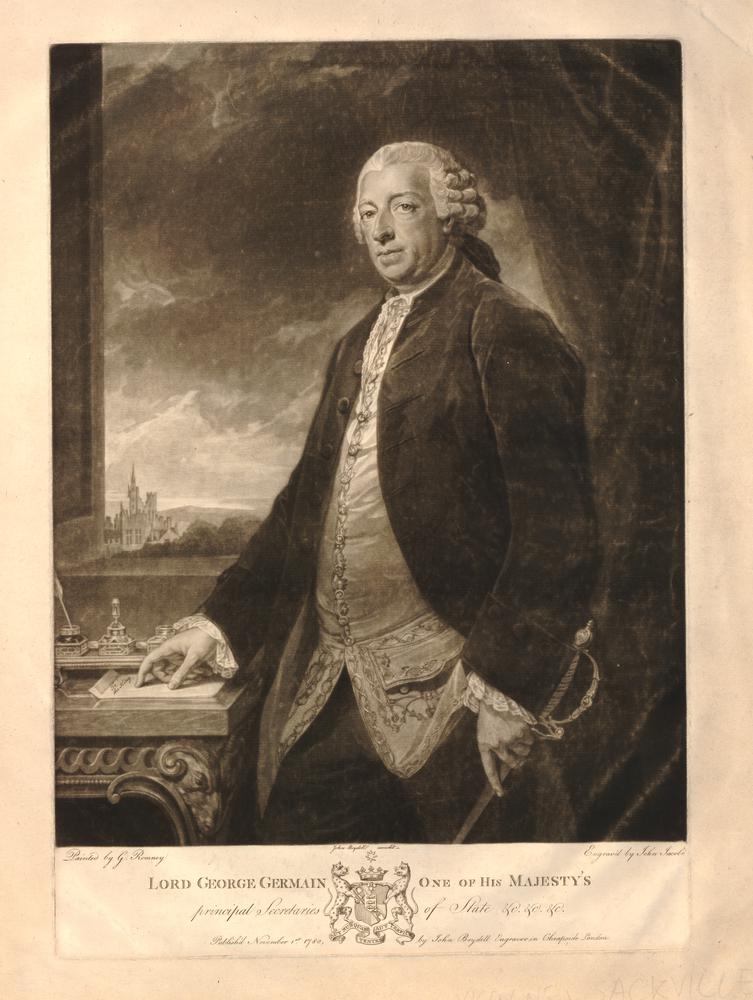

The man who Replaced Dartmouth as secretary of state for America was Lord George Germain, a younger son of the duke of Dorset. Horace Walpole described him as ‘of very sound parts, of distinguished bravery, and of an honourable eloquence, but hot, haughty, ambitious, obstinate’. [Walpole, Mems. of George II (Yale), i. 190]

In 1758 Germain (at that point known as Sackville) had been sent to Germany as second-in-command of the British forces and was later promoted commander-in-chief. At the battle of Minden on 1 August 1759, though, he failed to obey orders given by his superior, Prince Ferdinand of Brunswick, commander-in-chief of the Allied army, to lead the British cavalry against the shattered French forces. The prince charged him with disobedience, while Sackville held that he had received conflicting orders, often delivered in German, and had been stationed on difficult terrain. He was castigated as a coward, even a traitor, by the enemies he had gained by his high-handed behaviour. Ever self-confident, Sackville insisted on convening a court martial so he could justify himself. According to Walpole, ‘Nothing was timid, nothing humble, in his behaviour’ [Mems. of George II, iii. 101-105], but the court declared him ‘unfit to serve… in any military capacity whatsoever’.

The shame of Minden always hung over Sackville, and for the next decade and a half he worked to rehabilitate his reputation. His chances were improved by the death of George II, who had developed a violent personal dislike of him. Sackville looked forward to better treatment from George III, but even he was unwilling to take a disgraced soldier back into favour immediately. Sackville relied for his slow recovery on his service in the Commons, where he advocated a firm line against the colonists, arguing at one point that ‘The ministers… must perceive how ill they are requited for that extraordinary lenity and indulgence with which they treated… these undutiful children’.[HMC Stopford-Sackville, i. 119]

In 1769 Sackville took the surname Germain, after inheriting property from Lady Elizabeth Germain. He continued speaking against the colonists throughout the first half of the 1770s and on 7 February 1775 he was the Commons’ messenger to the Lords requesting a conference on the address declaring Massachusetts in rebellion. He seemed, thus, an obvious choice as North looked for a new direction in the morass of the American crisis. Walpole summarized the effect that the change had on the war and the ultimate loss in America: ‘Till Lord George came into place, there had been no spirit or sense in the conduct of the war… [He was] indefatigable in laying plans for raising and hiring troops’. [Walpole, Last Journals i. 511, ii. 49] Some contemporaries went so far as to suggest that Germain’s belligerence towards the Americans was an attempt to put to rest the shame of Minden. As Edward Gibbon put it, Germain hoped to ‘reconquer Germany in America’.

CGDL

Further reading:

P.D.G. Thomas, Tea Party to Independence: The Third Phase of the American Revolution, 1773-1776 (Oxford, 1991)

Andrew O’Shaughnessy, The Men who Lost America (Yale, 2013), esp. ch. 5

Alan Valentine, Lord George Germain (Oxford, 1962)

HMC Dartmouth

HMC Stopford Sackville, vols. I and II