In this latest post, the Georgian Lords welcomes a guest article by James Orchin, PhD student at Queen’s University, Belfast, re-examining William Windham’s ‘Third Party’, known as ‘The Alarmists’. The group was mostly made up of former Foxite Whigs, who had split from Fox over the French Revolution, and found itself positioned somewhat unhappily between Pitt the Younger’s administration and the Foxite opposition in the early 1790s.

On 10 February 1793, 21 Members of the Commons gathered at 106 Pall Mall. Over 50 had been expected only for the invitations to be sent out late. The attendees were mainly conservative Foxite Whigs, and all were horrified by events in France and the stance of Charles James Fox. They resolved to secede and form a ‘Third Party’ while providing qualified support for William Pitt’s Ministry. This secession, which augured the disintegration of the Foxites and the formation of the Pitt-Portland coalition, was pursued with considerable hesitation.

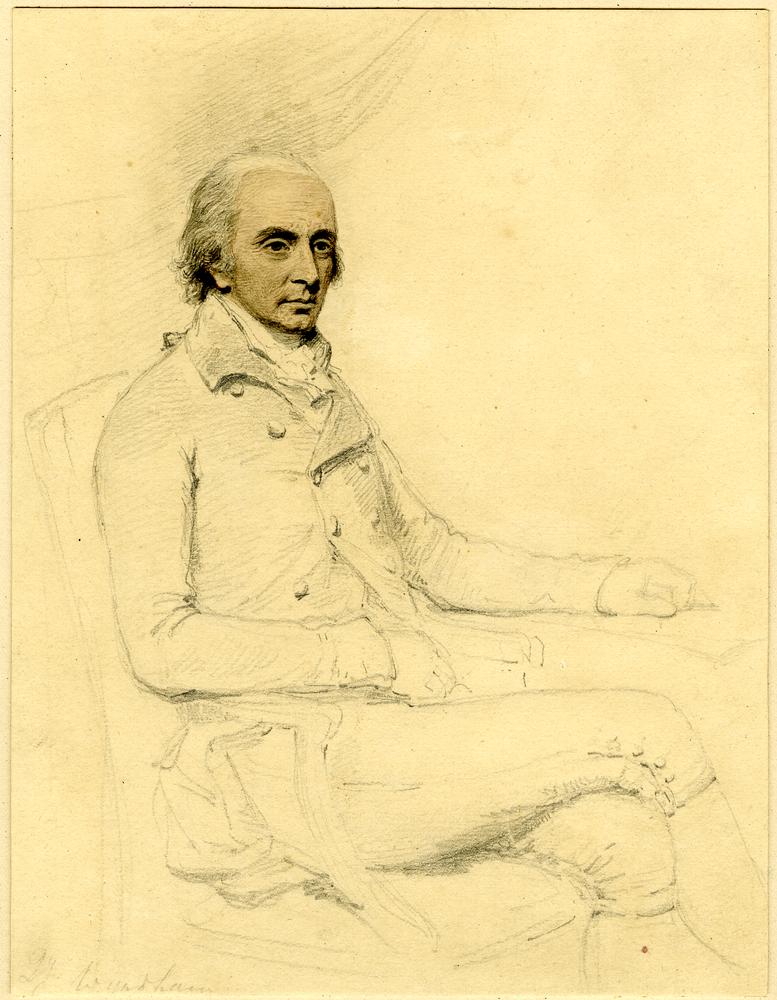

The anguished path towards secession was illustrated well in the man reluctantly acclaimed as leader, William Windham (1750-1810).

(c) Trustees of the British Museum

The scion of an old Norfolk family, Windham began his political career in 1778 with a well-received address opposing the American War. After a brief, difficult tenure as Chief Secretary for Ireland, he was returned as one of the Members for Norwich in 1784. Windham slowly grew into his role as a parliamentarian, occasionally crippled by anxiety and hypochondria, and first achieving note as one of the managers of the impeachment of Warren Hastings. Initially moderately liberal, Windham became increasingly conservative by the early 1790s, influenced by his close friend Edmund Burke.

Like many in the political nation, Windham was initially sympathetic to the French Revolution, visiting Paris in August 1789 and writing approvingly of the situation to Burke. Fox’s nephew, Lord Holland, thought him a ‘warm admirer’ of the Revolution. Windham was among a group of British visitors to Paris in August 1791 observing the formal ratification of the new Constitution, where the treatment of Louis XVI horrified him. Windham had come to France, as Lord Auckland recorded, ‘a great admirer’ of the Revolution and returned increasingly alarmed.

The schism of his close friends Burke and Fox over the Revolution by May 1791 anguished Windham profoundly. Like other conservative Foxites, he agreed privately with Burke, but was deeply reluctant to split from Fox and the Whigs’ de jure leader, the respected but indecisive conservative 3rd duke of Portland. By 1792 Windham was increasingly prominent as an anti-Jacobin, fostering social links with French royalist émigrés and supporting anti-sedition measures at home. Still, he was resistant to give way to secession, wishing that the Foxites ‘should act as cordially together as if no such difference had ever occurred’.

The increasing violence of the Revolution by 1792 and Fox’s continued sympathies eventually convinced conservative Foxites they could not sway Fox towards their position. With Portland more interested in avoiding a split, conservative Foxites looked increasingly to Windham for political direction. Fellow conservative Sir Gilbert Elliot opined in December that with Portland’s ‘indecision’, conservatives looked to Windham, who ‘stands higher at present, both in the House and in the country, than any man I remember’.

The execution of Louis XVI and the outbreak of war by early February 1793 finally provoked the secession with the aforementioned meeting of 10 February followed by another a week later. ‘The meeting has a good effect’, wrote Elliot:

It must show the Duke of Portland that we are determined to take our own line even without him; and it has pledged Windham more distinctly than he was before to a separation from Fox.

Despite this the ‘Third Party’ hoped to convince Portland to split from Fox and take ‘his natural place as our leader’. The seceders were thus forced into a curious situation of defecting from a faction whose nominal leader they still pined for. Their resolve was, however, demonstrated further with the secession of 45 men from the Whig Club in late February 1793.

Windham initially hoped for around 86 defectors, yet the number settled ultimately to 38, of which at most 28 were ex-Foxites. Of the 45 Whig Club seceders, 18 were MPs and only ten joined the Third Party. The party’s membership illustrates the Opposition’s ideological fluidity before the polarization of the 1790s. It included the ‘High Tory’ Foxite Sir Francis Basset; Lord North’s son Frederick North; John Anstruther, whose political trajectory mirrored Windham’s, and Thomas Stanley who abandoned his reformist-leaning sentiments after witnessing the storming of the Tuileries Palace. Crucially, however, prominent conservative Whigs such as Earl Fitzwilliam, Earl Spencer, Tom Grenville, and Portland opposed the move, considering Whig unity paramount.

Described by Elliot as ‘dilatory and undecided’, after this period of political activity Windham was initially a reluctant leader expressing to John Coxe Hippisley how ‘much against my will I have been obliged to act as a sort of head of a party’ nicknamed ‘as the sect of Alarmists’. Windham believed that if Portland continued to dither, they would ‘dwindle away and be dispersed in various channels till the very name and idea of the party will be lost’. Windham was finally roused into political action with his spirited opposition to Charles Grey’s motion on parliamentary reform in May 1793, after which he focused on urging Portland’s secession from Fox and preventing Pitt from poaching Alarmist MPs.

Under Windham the Alarmists pursued an independent line, providing outside support for Pitt while insisting that they would only rally to him as a collective and not individually. The latter, Pitt’s preferred strategy, had already seen Lord Loughborough (the future earl of Rosslyn) defect to become Lord Chancellor in January 1793, followed by other conservative Whigs such as Gilbert Elliot and future Member, Sylvester Douglas. Over summer 1793 Pitt attempted to coax Windham over to the Ministry with offers of high office, which Windham refused despite considerable pressure from Burke and others.

Windham persisted with his independent stance, stressing in August 1793 that a coalition was only possible ‘if others could surmount those objections’. September saw Windham appeal to Portland to lead his followers from Fox, feigning a wish to be ‘a mere member of Parliament’. He stressed that a Whig reunion was impossible and that the only options were to ‘remain a third body’ or join en masse with Pitt. Portland continued awkwardly to affirm his support for the war and opposition to Pitt.

Conservative horror was heightened further by the execution of Marie Antoinette in October and the fall of Toulon in December. Realizing the inefficacy of his stance, Portland finally led an exodus of 51 MPs. The Portlandites adopted the independent line at a meeting attended by Windham and Burke and joined the Third Party, now under Portland’s leadership. ‘Being able to form an independent Party under so very respectable a head’, Frederick North expressed to Windham, was ‘the most desirable political Event’. Despite Portland assuming leadership, though, Windham remained a significant presence.

With around 77 former Whigs among their ranks, the seceders now outnumbered the remaining 66 Foxites. What had begun with a mere 21 MPs in Pall Mall had grown to include over half of all Foxite Whigs. Despite some individual defections to Pitt, Windham’s line of ‘no longer answer[ing] separate’ remained. After negotiations, a Pitt-Portland coalition was agreed with the new ministers receiving their seals on 11 July, Windham among them as Secretary at War.

While short-lived, the party ultimately succeeded in its central objectives. An independent, hawkish, conservative Whig faction was later seen in the form of the Grenvillite ‘New Opposition’, which opposed Henry Addington’s Ministry from 1801. That stridently anti-peace faction was led in the Commons, perhaps unsurprisingly, by the resident of 106 Pall Mall.

JO

Further Reading

Herbert Butterfield, ‘Charles James Fox and the Whig Opposition in 1792’, The Cambridge Historical Journal, ix (1949), 293-330.

Leslie Mitchell, Charles James Fox and the disintegration of the Whig Party, 1782-1794 (1971).

Frank O’Gorman, The Whig Party and the French Revolution (1967).

Max Skjönsberg, The Persistence of Party: Ideas of Harmonious Discord in Eighteenth-Century Britain (Cambridge, 2021).

David Wilkinson, ‘The Pitt–Portland Coalition of 1794 and the Origins of the ‘Tory’ Party’, History, lxxxiii (1998), 249-64.