Amongst his many endeavours, John Gully’s venture into politics was an unexpected, yet successful, career choice. In this article Dr Kathryn Rix of our House of Commons, 1832-1945 project explores Gully’s life, from his humble beginnings to his sporting fame and his election as MP for Pontefract following the upheaval of the 1832 Reform Act.

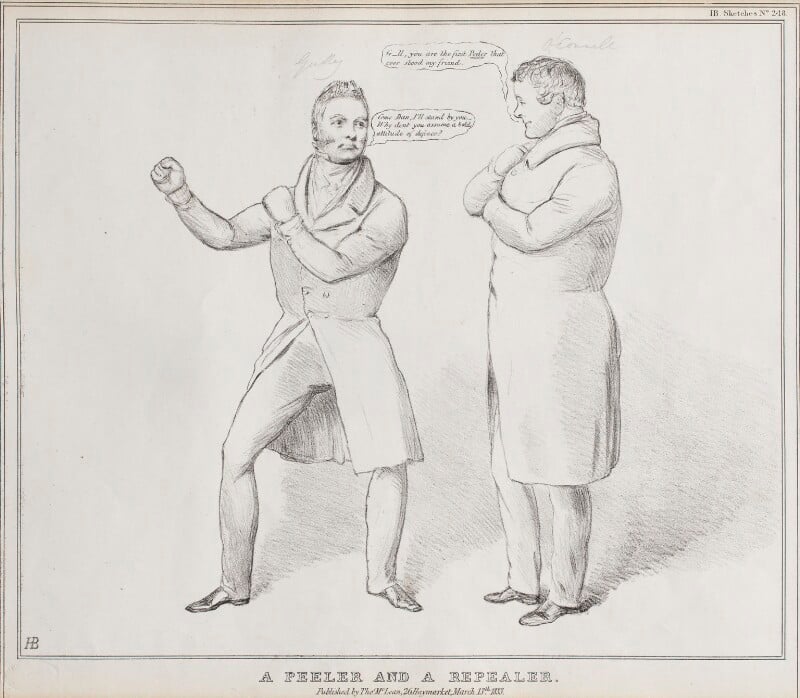

In March 1833 the cartoonist ‘H.B.’ (John Doyle) chose three newly elected MPs to represent the ‘March of Reform’, depicting them entering the House of Commons under the suspicious glances of four former Tory MPs. These three were the noted radical journalist William Cobbett, returned for Oldham at the 1832 general election; the Quaker industrialist and railway entrepreneur Joseph Pease, elected for Durham South; and perhaps the most unlikely parliamentarian of all, John Gully (1783-1863), ‘an advanced reformer’, who served as MP for Pontefract for five years from 1832.

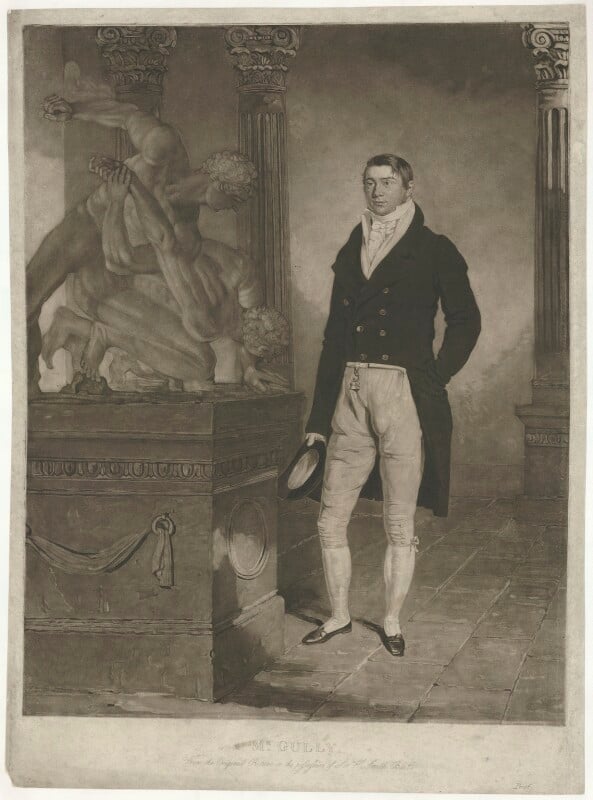

In a parliamentary sketch, Charles Dickens described this

quiet gentlemanly-looking man in the blue surtout, grey trousers, white neckerchief, and gloves, whose closely-buttoned coat displays his manly figure and broad chest to great advantage.

Gully’s gentlemanly demeanour in the Commons gave little hint of his extraordinary background. The son of a Gloucestershire innkeeper, he had been in turn a butcher, imprisoned debtor, champion pugilist, pub landlord, professional betting man and racehorse owner, and fathered 24 children (by two wives). Indeed his return to Parliament seemed so incongruous that it was rumoured that he had only sought election to win a bet.

Gully was born in his father’s pub near Bristol in 1783. When his father opened a butcher’s shop in Bristol, he trained Gully in this trade. Subsequent financial difficulties saw Gully imprisoned for debt in London’s King’s Bench prison. However, he secured his release in 1805 after his debts were paid by prize-fight promoters. They had noted Gully’s prowess in a brief fight against his Bristol acquaintance, Henry Pearce, a champion prize-fighter, and were keen for the pair to fight a proper match. Six feet tall, with an ‘athletic and prepossessing’ frame, Gully lost their bout at Hailsham, Sussex, at which the future William IV was among the numerous spectators. When Pearce retired later that year, Gully was regarded as his successor as ‘champion of England’, and won notable fights in 1807 and 1808, before quitting to become landlord of a London pub.

Described as ‘second to none’ as a judge of racehorses, Gully became a professional betting man on the Turf, making his own wagers and taking commissions for others. He acquired his own racehorses in 1812, and in 1827 moved to Newmarket to pursue this more seriously. He won (and lost) huge sums through gambling: he and his business partner were said to have made £90,000 when their horse won the 1832 Derby. Although one contemporary claimed that Gully was ‘a regular blackleg’, the general consensus was that, in contrast with most of those involved with betting on the Turf, Gully was notably honourable and straightforward.

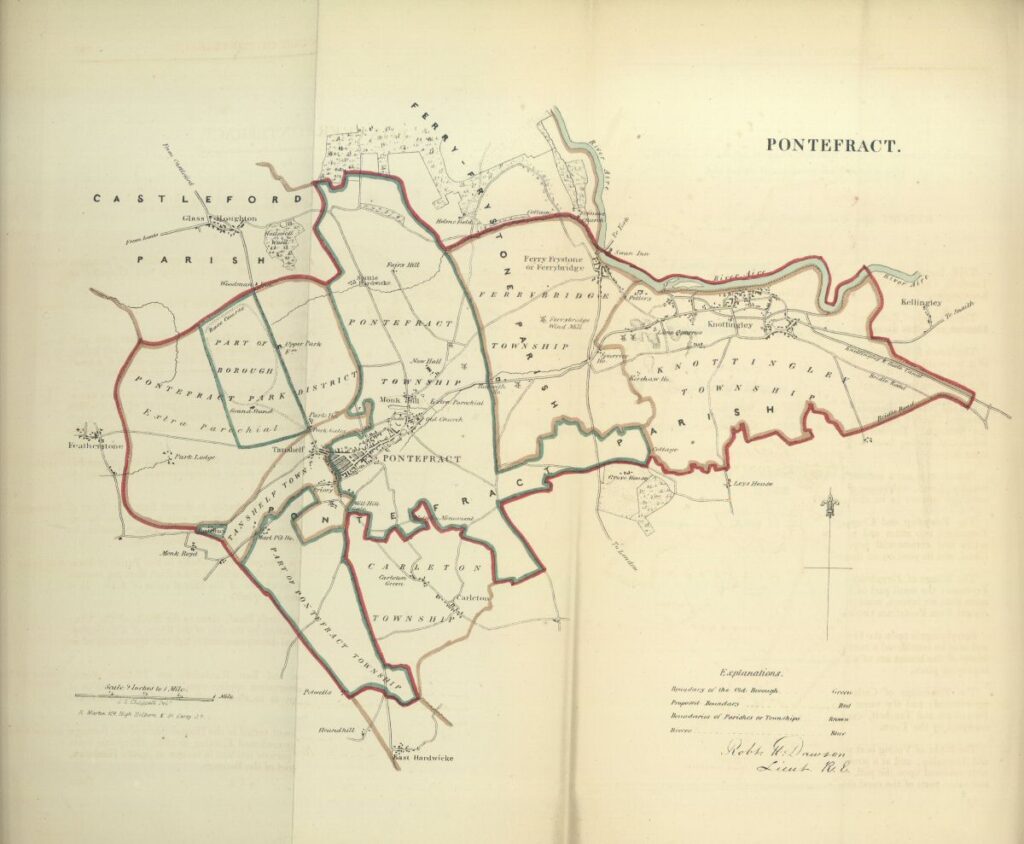

Continuing his upward social trajectory, Gully bought Ackworth Park, near Pontefract, in 1832, and invested in coal mines in northern England, which brought him ‘immense profits’. (He left a fortune of £70,000 on his death in 1863.) The Reformers of Pontefract invited their new neighbour to stand as their candidate at the general election in December 1832. Visiting the town to decline their invitation, Gully was so angered by comments by their Tory opponents that he changed his mind and decided to stand. He was elected unopposed as one of Pontefract’s two MPs.

The diarist Charles Greville, while listing him among the ‘very bad characters’ returned to the first Reformed Commons, conceded that despite being ‘totally without education’, Gully had ‘strong sense, discretion, reserve, and a species of good taste’ and had ‘acquired gentility’. When Gully was presented at court by Lord Morpeth in 1836, another contemporary described this as ‘an instance of the levelling system now established in England’.

Although Gully rarely spoke in the Commons, he was a diligent attender who served on several select committees. He was often found in the minorities voting with Radical and Irish MPs in support of reforms such as the ballot, the removal of bishops from the House of Lords, the abolition of flogging as a punishment in the army and reform of the corn laws. He was re-elected in 1835, but retired in 1837 as the ‘late hours’ sitting in the Commons had damaged his health. He stood again at Pontefract in 1841, when he declared himself ‘the enemy of all monopolies, and the friend of the poor’, but retired early from the poll.

Despite this defeat, Gully remained politically active. Given his humble origins, it was perhaps unsurprising that he was sympathetic to the demands of the Chartists for parliamentary reform, although he disliked their violent tactics. He was also a keen supporter of the Anti-Corn Law League. He continued to enjoy considerable success as a racehorse owner, and the Manchester Times recorded in 1846 that ‘few men are more popular on the English race course, or more approved of by the aristocracy of the land’. The parliamentary career of this sporting celebrity demonstrates the ways in which those from non-elite backgrounds could find their way into the post-1832 House of Commons.

This is an updated version of an article originally published on the Victorian Commons website on 23 November 2016, written by Dr Kathryn Rix.