A recent article in this series [Background to the American Revolution] looked at the debates in the House of Lords in early February 1775 on a bill for conciliation with the American colonies. After its rejection the imperial crisis continued to occupy the House’s attention. In the latest post for the Georgian Lords, Dr Charles Littleton considers the debates and divisions occasioned by the addresses, motions, and bills which persisted into the spring.

On 7 Feb. 1775 the House of Lords considered an address from the Commons claiming for the first time that ‘a Rebellion at this time actually exists’ in the Massachusetts Bay colony. The inflammatory language was accepted, and in consequence a bill to restrain the trade of the Massachusetts Bay colony was introduced. Both its committal at second reading on 16 March and its eventual passage five days later led to violent debate. Another bill to extend trading restrictions to the colonies south of Massachusetts was debated at third reading on 12 April.

Inevitably, events on the ground in America overtook many of these discussions, as on 19 April American militiamen and British troops exchanged gunfire at Lexington and Concord. Crucially, news of their confrontation did not reach Britain until the end of May, and the House continued unaware that armed conflict had already begun. On 17 May Charles Pratt, Baron Camden, brought in a bill to repeal the Quebec Act, one of the so-called Coercive Acts of 1774. The government’s motion to reject the repeal bill occasioned yet another debate.

In all, these matters occasioned eight divisions in the Lords between 7 February and 17 May 1775. The government won every one handily, with the numbers in the minority ranging between 21 and twenty-nine. In other words, there was a core of about 22 lords who consistently opposed the government’s bellicose policies towards the colonies during the tense spring of 1775. Both then and in the years following, the opposition’s main concern was domestic, as they fought against what they saw as the corruption, ‘secret influence’, and tendency to arbitrary rule of George III’s government.

The opposition used the ministry’s mismanagement of the American crisis as a means to attack the Crown and seek for ‘new measures and men’ in government. With a few exceptions, however, they did not apply themselves to addressing the substantive constitutional questions raised by the colonists.

There were some within the opposition who came close to an actively pro-American stance, or at least made an attempt to understand the colonists’ complaints, such as Willoughby Bertie, 4th earl of Abingdon. Charles Lennox, 3rd duke of Richmond, also took a ‘radical’ Whig stance both in 1775 and for the following 30 years, and remained one of the most frequent, and forceful, speakers for the opposition.

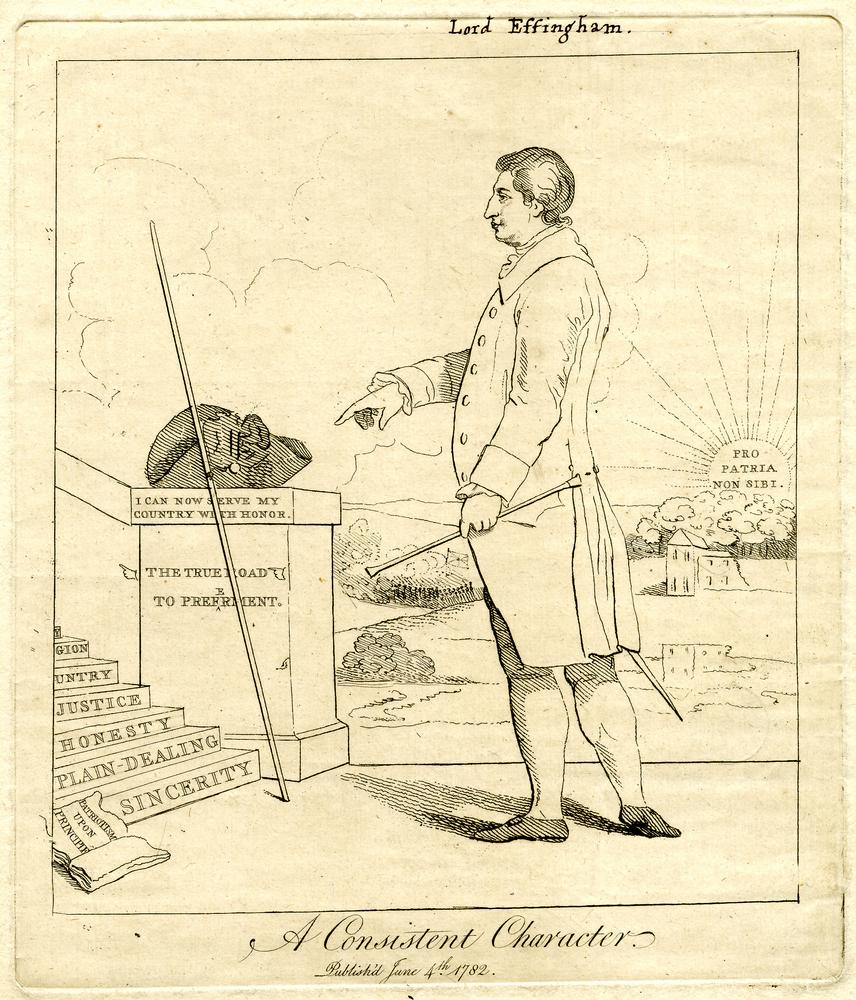

A third, was Thomas Howard, 3rd earl of Effingham, who was summed up by Horace Walpole as ‘a rough soldier, of no sound sense [Walpole’s Last Journals, i. 439]. As a captain in the 22nd Foot Regiment, Effingham had adopted a pro-American stance as early as 1774. On his estates near Rotherham, he built a hunting lodge which he dubbed Boston Castle, where he forbade the drinking of tea, in honour of the Boston Tea Party.

Throughout the spring of 1775 Effingham acted with the opposition, acting as a teller for the minority in three of the eight divisions. On 18 May the government sought to block an opposition motion that a memorial from the New York Assembly should be read out. Effingham intervened, but quickly turned away from the technical procedural issues with which the House was embroiled. He made clear his sympathy with the colonists, declaring ‘Whatever has been done by the Americans I must deem the mere consequence of our unjust demands’. He predicted imminent bloodshed (which, of course, had already occurred), for all it would take was ‘a nothing to cause the sword to be drawn and to plunge the whole country into all the horrors of blood, flames and parricide’. He then turned to himself. Speaking of his love for the military life, he confessed that he now found himself bound to resign his commission in the Army, as:

‘the only method of avoiding the guilt of enslaving my country and embruing my hands in the blood of her sons. When the duties of a soldier and a citizen become inconsistent, I shall always think myself obliged to sink the character of the solider in that of the citizen, till such time as those duties shall again, by the malice of our real enemies, become united’. [John Almon, Parliamentary Register, vol. 2 (1774-5). 154-56].

Effingham was briefly the toast of the country for his act of self-sacrifice. Walpole was asked, ‘Was there ever anything ancient or modern better either in sentiment or language than [Effingham’s] late speech?’. [Walpole Corresp., xxviii. 208-9] Although Walpole thought that Effingham ‘was a wild sort of head’, he admitted the intervention had been ‘very sensible’. [Walpole’s Last Journals, i. 466] Effingham was apparently a bit of a showman. It was widely reported that in a dramatic conclusion, he flung his sword clattering down on to the floor of the House.

Effingham’s speech was the last in this particular debate, and at 8.30 at night the House rejected hearing the memorial from New York. Parliament was prorogued a week later, about the time news of the armed confrontation at Lexington reached Britain. That changed everything, and although the Second Continental Congress made one last-ditch effort at peace with its ‘Olive Branch Petition’ of 8 July, the king rejected it out of hand. On 1 August he issued a royal proclamation declaring that the colonists were ‘engaged in open and avowed rebellion’. The declaration left Britain and the American colonists formally at war.

CGDL

Further reading:

John Almon, The Parliamentary Register, vol. 2, (1775)

Frank O’Gorman, ‘The Parliamentary Opposition to the Government’s American Policy, 1760-1782’, in H. T. Dickinson (ed.), Britain and the American Revolution (1998), pp. 97-123

Alison Olson, The Radical Duke: The Career and Correspondence of Charles Lennox, 3rd duke of Richmond (1961)