At the IHR Parliaments, Politics and People seminar on Tuesday 25 November, Dr Natalee Garrett of The Open University, will be discussing Jane, duchess of Gordon and the Romanticisation of Scottish Identity in London, c.1780-1812.

The seminar takes place on 25 November 2025, between 5:30 and 6:30 p.m. It will be hosted online via Zoom. Details of how to join the discussion are available here.

‘The Tartan rage has at length reached Paris,’ declared the World in June 1787. Demand for tartan fabric and accessories had swept British high society earlier that year, with the Gazetteer and New Daily Advertiser reporting in March that ‘the tartan plaid has obtained a complete triumph over every other ribband.’

Not everyone was pleased to see tartan becoming a fashion must-have: in March 1787 The Times archly commented that plaid ‘reminds us of the irritating constitutional disorder of its ancient wearers,’ a remark which highlights entrenched negative views of Scottish identity and history.

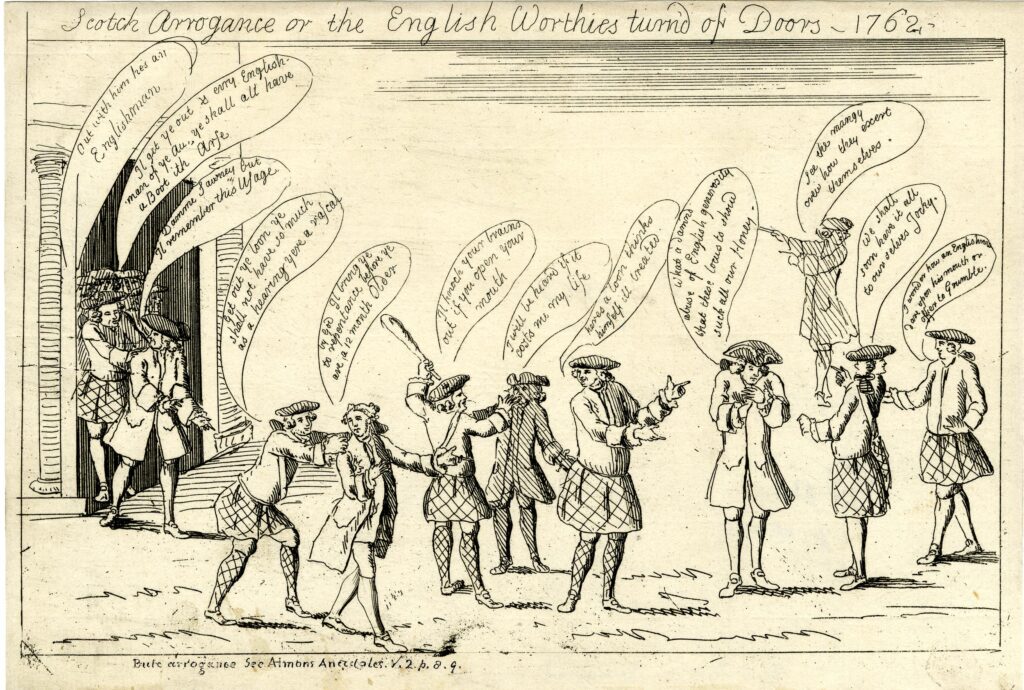

Some of this history was recent: during the Jacobite Rising of 1745, plaid had become indelibly intertwined with rebellion in many English minds. In the 1760s, tartan had developed a further negative connotation in England, being used in satirical images to identify the unpopular 3rd earl of Bute, a Scotsman who acted as Prime Minister between 1762 and 1763. In many of these prints (such as Figure 1) Bute was accused of advancing his fellow Scots at the expense of English politicians.

Despite its historic connotations in England, by the spring of 1787, every fashionable woman in London wanted to be seen with a bright plaid ribbon encircling her waist. Who was behind this Scottish fashion revolution?

Born the daughter of an impoverished baronet in Galloway, southwest Scotland, Jane Maxwell leapt up the social ladder when she wed Alexander, 4th duke of Gordon, in 1767. Having spent her teenage years rubbing shoulders with leading figures of the Scottish Enlightenment in Edinburgh, Jane’s social acumen saw her rise to become one of Georgian Britain’s foremost society hostesses, alongside her friend and rival, Georgiana, duchess of Devonshire.

Where Georgiana supported the Opposition, Jane was a supporter of the government, led by William Pitt the Younger. Nathaniel Wraxall, a writer and politician, remarked that Pitt’s government ‘did not possess a more active or determined partisan’ than the duchess of Gordon.

Having already cultivated her reputation as a leading society hostess and patroness in Scotland, in the mid-1780s Jane began to spend more time in London, where she astonished contemporaries with her hectic social calendar. After recounting a long list of Jane’s activities on a single day, the writer Horace Walpole remarked: ‘Hercules could not have achieved a quarter of her labours in the same space of time.’ Jane also hosted many gatherings of her own and she quickly established her reputation as a leading society hostess in the capital.

Society hostesses like Jane participated in what Elaine Chalus has called ‘social politics’. Namely, ‘the management of people and social situations for political ends’. Social politics gave aristocratic women the chance to participate in a political system from which they were officially excluded. For these women, the home was an important site of political networking. Outside the halls of Parliament, balls, visits, and dinners were opportunities for political discussion and alliances to flourish.

Jane was best known for hosting ‘routs’, gatherings which were more informal than balls, but which also tended to feature dancing, card-playing, and plenty of gossip. At these events, Jane’s guest lists comprised individuals from the highest echelons of British society, including the Prince of Wales and his brothers. One of Jane’s most extravagant events took place in February 1799, when the Courier reported that she had hosted ‘between five and six hundred personages of the highest rank and fashion’ at her home in Piccadilly.

When the trend for tartan swept London’s high society in 1787, it was evident that the duchess of Gordon was responsible. Jane continued to incorporate tartan elements in her clothing, including at Court celebrations for Queen Charlotte’s birthday in 1788, and again in 1792. At the latter event, Jane wore a tartan gown made from Spitalfields silk, setting off yet another frenzy for tartan in the capital.

Five months later, Isaac Cruikshank produced a print titled ‘A Tartan Belle of 1792’ (see Figure 2). It showed a lady (probably Jane herself) bedecked in tartan fabric. Far from a simple fashion statement, Jane’s endorsement of tartan was part of a wider campaign to popularize Scottish identity and culture.

Jane distinguished herself from rival society hostesses by placing her Scottish identity front and centre at her events. In May 1787, The Times reported that 500 guests of the first rank were invited to a ‘tartan ball and supper’ at Jane’s London residence.

At Jane’s parties, Highland dancing and music were the main entertainments, and guests were encouraged to wear ‘Highland’ dress. The trend for tartan among aristocratic women eventually spread to the men. In June 1789, the Star and Evening Advertiser reported that the Prince of Wales would ‘shortly appear in Highland dress’ at an upcoming ball.

Jane’s persistent assertions of her Scottish identity through fashion had provoked criticism in some quarters, yet her advocacy for Scottish dance was viewed in a more positive light. In October 1808 La Belle Assemblée or Court and Fashionable Magazine praised Jane for making Highland dancing popular at high society events, because it discouraged people from gambling in high-stakes card games.

The popularity of Scottish dance was undeniable and many other society hostesses began to integrate reels and strathspeys into their events. Scottish dancing even received the royal seal of approval. In 1799, Jane’s two eldest children were asked to perform in front of the king and queen at a fête at Oatlands Palace.

By blending her Scottish identity with her role as a society hostess, Jane helped to shift preconceived notions of Scottishness in Georgian England. Once viewed as symbols of rebellion, markers of Scottish identity like tartan and Highland dancing became fashionable in London’s high society thanks to the influence of the duchess of Gordon.

NG

Natalee’s seminar takes place on 25 November 2025, between 5:30 and 6:30 p.m. It will be hosted online via Zoom. Details of how to join the discussion are available here.

Further reading:

E. Chalus, ‘Elite Women, Social Politics, and the Political World of Late Eighteenth-Century England’, The Historical Journal 43:3 (Sep. 2000), 669-697

W. S. Lewis (ed.), The Yale Edition of Horace Walpole’s Correspondence, 48 vols (1937-83)

H. Wheatley (ed.), The Historical and the Posthumous Memoirs of Sir Nathaniel William Wraxall, 5 vols (1884)