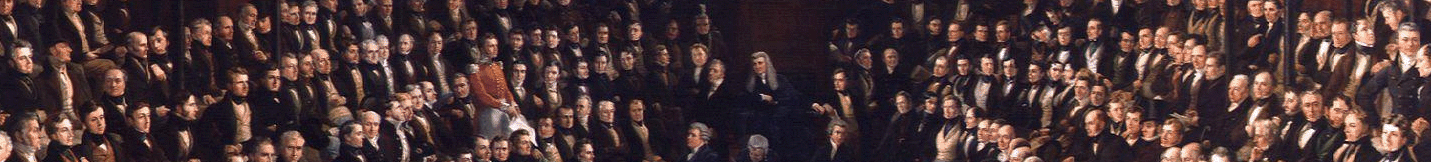

Our Victorian Commons project is shedding new light on the increasingly important role played in the behind-the-scenes business of the post-1832 House of Commons, particularly in the committee-rooms, by MPs who came from non-elite backgrounds. Dr Kathryn Rix looks at the life and career of Daniel Gaskell (1782-1875), including his friendship with the author Mary Shelley.

Described by the novelist Mary Shelley as ‘a plain silentious but intelligent looking man’, Gaskell served as MP for Wakefield from 1832 until his defeat in 1837. Whilst a family inheritance enabled him to lead a comfortable life as a country gentleman, his Unitarian faith set him apart from the traditional political class. He was enthusiastically supported in his parliamentary career by his wife, and the often under-valued political role of women is another major theme to emerge in our research.

Gaskell was one of around 40 Unitarians who sat in the Commons during the 1832-68 period. His grandfather, a linen draper, and his father, a merchant, had both worshipped at Manchester’s Cross Street Unitarian Chapel. Gaskell was born in Manchester, but moved to Lupset Hall, near Wakefield, following his marriage in 1806. He and his older brother Benjamin were the major beneficiaries under the will of their cousin, James Milnes, and acquired considerable urban and rural property. Lupset Hall ‘received all the embellishment which taste and art could confer upon it’ and became ‘the seat of the most liberal hospitality’. Gaskell was acquainted with prominent figures such as the philosopher and social reformer Jeremy Bentham, although Mary Shelley considered him and his wife to be ‘country folks in core’.

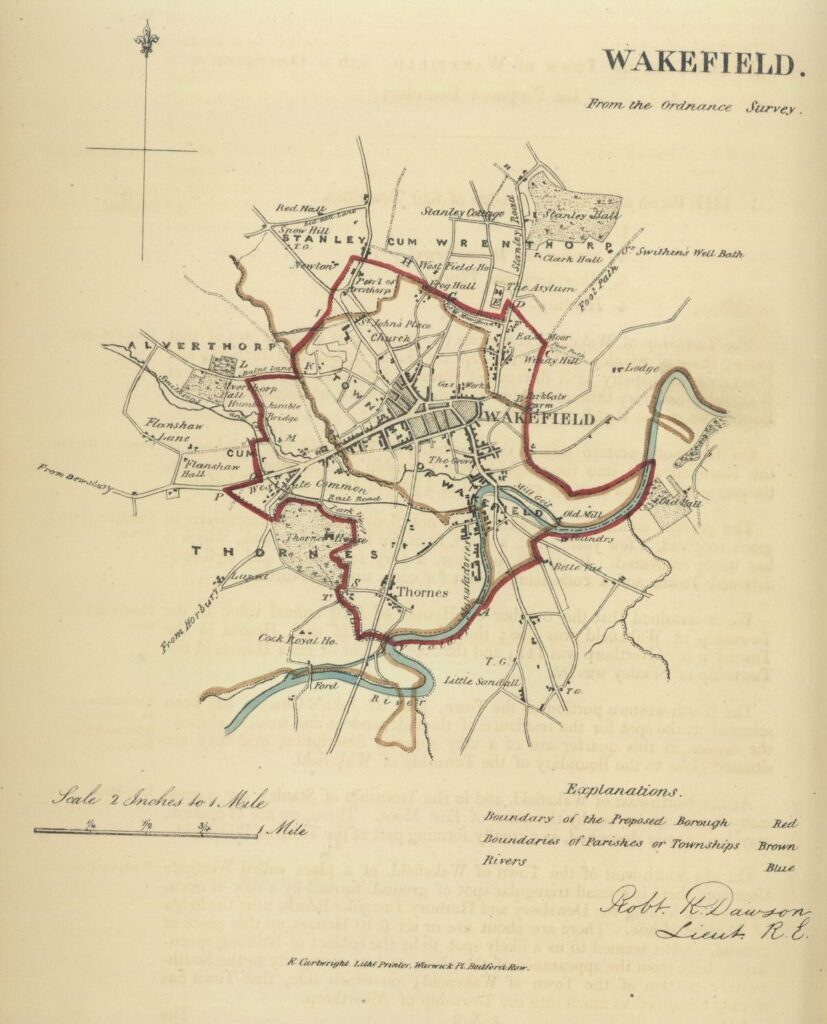

The Radicals in the newly enfranchised borough of Wakefield – which had one MP from 1832 – invited Gaskell to be their candidate. He initially accepted, but subsequently withdrew. He was, however, persuaded to reconsider. In August 1831, his nephew, James Milnes Gaskell, who had begun canvassing Wakefield as a Conservative, recorded that ‘the radicals had so effectually worked upon my uncle’s anxious and sensitive mind that he considered it a point of conscience’ to stand. Milnes Gaskell withdrew in his uncle’s favour in March 1832, finding a safe seat at Wenlock instead. Gaskell was elected unopposed in December 1832, when his political platform included retrenchment in public spending, shorter Parliaments, the secret ballot, the abolition of slavery, revision of the corn laws and reform of the Church.

Alongside local Radical pressure, Gaskell’s formidable wife, Mary, played an important part in encouraging her ‘reluctant spouse’ to stand. Although women were debarred from the parliamentary franchise, their political influence in this period should not be overlooked, whether as local voters, petitioners, electoral patrons or, in Mary Gaskell’s case, political wives. ‘Unquestionably a character’, who ‘drew upon herself a great degree of notice from the leading part she took in public matters’, she was described as ‘a sort of zealot in the patronage of ultra-Liberals’. She went to hear sermons from the Unitarian preacher, William Johnson Fox (later Radical MP for Oldham), and ‘was a kind and generous friend’ to the radical journalist and novelist William Godwin and his family, including Mary Shelley, who was his daughter. In April 1831 James Milnes Gaskell told his mother that ‘it is, in fact, my Aunt, that would be member of Parliament’.

Despite his initial reluctance to stand, Gaskell was ‘punctual in his attendance’ at Parliament. Mary Shelley marvelled that

he attends the house night after night and dull committees and likes it! – for truly after a country town and country society, the dullest portion of London seems as gay as a masked ball.

Despite her comments about Parliament’s dullness, Shelley took advantage of her friendship with Gaskell to make use of his parliamentary franking privileges, encouraging correspondents to send letters to her via Gaskell, who could receive them without payment.

Although he was assiduous in his attendance, Gaskell seldom spoke in debate. One obituary recorded that ‘the atmosphere of publicity’ was not ‘congenial to his tastes and habits’. He was, however, remembered as ‘an excellent committee-man’, highlighting the fact that contributions in the chamber were only one aspect of parliamentary engagement. While Gaskell gave general support to Whig ministers, he expressed concerns that they ‘did not proceed in the path of Reform so rapidly as was generally expected; indeed some of their early measures seemed to indicate a retrograde movement’. Reflecting his claim that ‘I have attached myself to no party’, Gaskell’s votes in the division lobbies displayed considerable independence. He often divided in the minority with Radical and Irish MPs, on issues ranging from the ballot to the introduction of a moderate fixed duty on corn. His radical leanings prompted joint Whig-Conservative efforts to find an opponent to him at the 1835 election. He survived this contest, but was defeated in 1837. His parliamentary service was rewarded with the presentation of ‘two massive pieces of silver plate’ in 1838: a vase from the ‘ladies’ of Wakefield and a soup tureen from 1,700 male subscribers.

After several years’ absence from the Commons, Gaskell reluctantly agreed in December 1845 that he would stand again for Wakefield to support the cause of free trade. With the general election delayed and the corn laws repealed, he withdrew in April 1847 on grounds of his age and health. Widowed the following year, he subsequently dedicated his energies – and up to half his annual income of £4,000 – to charitable works. He was a particularly generous benefactor to the Unitarian church, donating £1,000 in 1856 to assist poorer congregations in the north of England. He also supported educational causes, contributing £3,000 towards new premises for the Wakefield Mechanics’ Institute in 1855. He died in December 1875.

This is an updated version of an article originally published on the Victorian Commons website on 27 June 2016, written by Dr Kathryn Rix.