Untangling the eclectic career of Benjamin Rotch (1793-1854), Whig MP for Knaresborough, 1832-5, proved to be an extremely interesting piece of research for Dr Kathryn Rix of our House of Commons, 1832-1945 project, taking in the Nantucket whaling industry, the complexities of patent law, prison reform and a challenge to a duel.

A quirky character, described by one contemporary as a man who ‘would resort to any wily expedient to attain his own ends’, Benjamin Rotch (1793-1854) provides a good example of the varied backgrounds and experiences of the new intake of MPs returned at the first general election after the 1832 Reform Act.

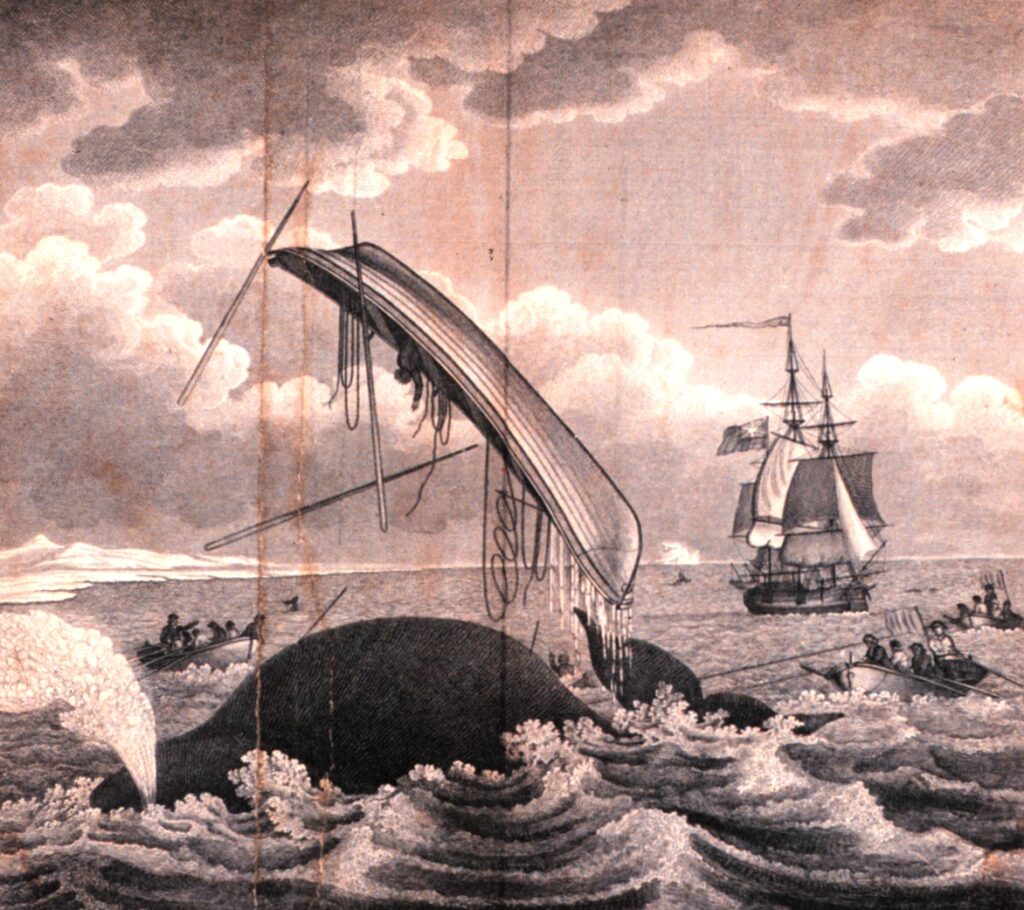

The Rotch family had emigrated from England to Massachusetts, where they rose from humble beginnings to become the most influential figures in the colonial whaling industry by 1750. However, the American revolutionary war’s adverse effects and the imposition of a punitive British tariff on whale oil in 1783 led many whalers to relocate. Rotch’s grandfather William, ‘by far the richest man on Nantucket’, transferred his activities to Dunkirk in France, where Rotch was born in 1793. Following the outbreak of war between France and England, his father moved the family to London. Later reports that Rotch and his mother had escaped from France hidden in a butter firkin and a flour barrel were refuted by his brother.

Rather than entering the family business, Rotch trained as a barrister, qualifying in 1821. He also became involved in other ventures. He took out patents, including one for a rubber horseshoe, and designed the prize-winning ‘Arcograph’, which allowed arcs of large circles to be drawn and measured. In collaboration with a Mr. Bradshaw, Rotch ended the monopoly of hackney coaches in London by acquiring licences to operate the cheaper and faster cabriolets in 1823, only to sell his interest the following year. He achieved financial success with his ‘patent lever fid’, a device to assist with striking and raising the topmast of ships. As a barrister he specialised in cases on patent rights and was an expert witness to the 1829 select committee on the patent laws.

Rotch first considered entering Parliament in 1826, when, in contrast with his later views, he canvassed Sudbury as a ‘true blue’. However, he withdrew amidst allegations that another candidate had bought him off. In 1830 he assisted the campaigns of Tory candidates at Knaresborough and Evesham. However, at the 1831 election he supported the Whig Sir James Mackintosh at Knaresborough, making a speech which Mackintosh presciently described as being ‘chiefly calculated to obtain a seat in the reformed Parliament’.

In 1832 Rotch stood as a Whig at Knaresborough, where he fought an acrimonious battle for the second seat with another Whig, Henry Rich. When Rotch emerged victorious, Rich petitioned against him on the grounds that he was an alien, having been born in France of American parents. However, Rich had to withdraw the case after difficulties obtaining documents from France. Although Rotch had, like his family, been a Quaker, he was not practising by 1832; it was therefore Joseph Pease who was the first Quaker MP to take his seat at Westminster.

An active MP, Rotch somehow managed to combine his parliamentary duties with the unpaid position of chairman of the Middlesex quarter sessions, sitting in court at Clerkenwell each day from 10 a.m. until 5 p.m., before going to the Commons after dinner. In one year alone he claimed to have tried 1,570 cases, handled 100 appeals and sat for 125 days. This prompted him to speak self-interestedly in support of proposals for Middlesex to become the only county which paid its chairman, but these did not bear fruit.

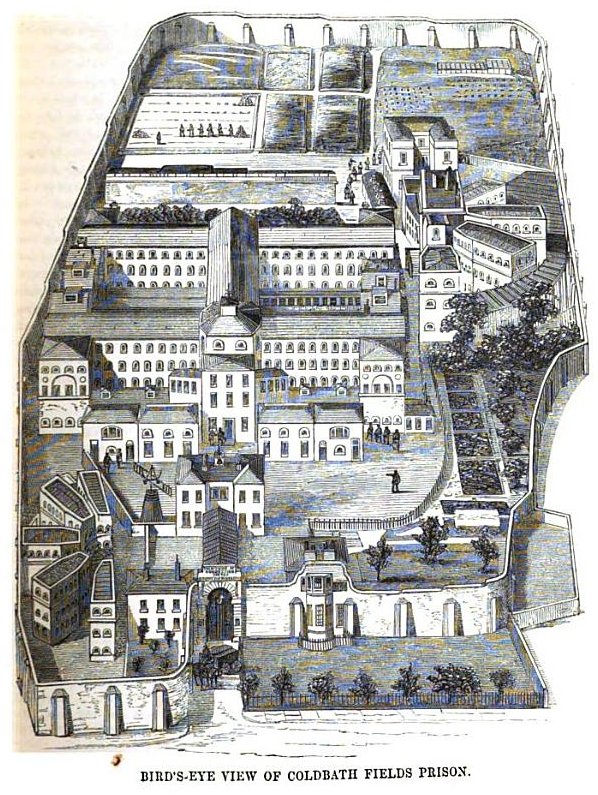

His expertise led Rotch to serve on several select committees on legal matters, such as the laws of inheritance. He assisted with drafting a bill on patents, although the measure subsequently stalled. Reflecting his earlier interests as a cab proprietor, Rotch moved without success in July 1833 for an inquiry to consider regulating the conduct of drivers of cabriolets, hackney coaches, omnibuses and stage coaches. Drawing on his experience on the bench, he took a sustained interest in crime and punishment, being particularly concerned about the poor state of prisons such as Newgate. He unsuccessfully attempted to pass legislation to confiscate the property of convicted felons in order to compensate their victims and defray imprisonment costs. His desire to pass a bill to protect workers who did not wish to join trades unions cost him support in his constituency, and he stood down in 1835.

After leaving the Commons Rotch continued his legal practice and remained chairman of the Middlesex quarter sessions. In October 1835, however, he became embroiled in a dispute which culminated in his resignation from the post. In evidence to a Lords inquiry on prisons, Rotch had condemned Newgate as ‘one of the most ill-conducted gaols in the country’ and accused London’s lord mayor and aldermen of only accepting into the gaol ‘such county prisoners as are, by the fees paid on their trial and conviction, likely to enrich the City purse’. A war of words prompted Rotch to challenge the lord mayor, Alderman Winchester, to a duel. Winchester responded by filing charges against Rotch for trying to incite a breach of the peace. Admitting that no provocation could have justified his actions, Rotch resigned as chairman in December and the charges against him were dropped after he apologised.

Despite this incident, Rotch remained active as a magistrate and took a keen interest in prison reform. In 1849, at his own cost, he sent sheep into Cold Bath Fields prison, hoping to train prisoners for new careers as shearers in Australia. This, combined with his zeal for teetotalism, on which he lectured prisoners and prison staff, led to him being mocked as ‘Drinkwater Rotch, the Sheep-shearing Magistrate’. He continued to dabble in a variety of projects, such as drafting an insurance scheme for railway passengers and taking out a patent for the manufacture of artificial saltpetre, until his death on 31 October 1854.

This is an updated version of an article originally published on the Victorian Commons website on 31 October 2015, written by Dr Kathryn Rix.