In this guest article Dr Joe Cozens discusses his research into John Lewis, a Black sailor who was arrested during the 1828 Weymouth by-election. Dr Cozens is a Nineteenth Century Social and Political Records Researcher at The National Archives, Kew.

On the eve of the February 1828 Weymouth and Melcombe Regis by-election, a Black seaman named John Lewis was arrested for being ‘at the head of a mob chiefly composed of boys’. Anxious to preserve the ‘peace of the town’, the mayor and magistrates of Weymouth decided to commit him to the county gaol for a month of hard labour.

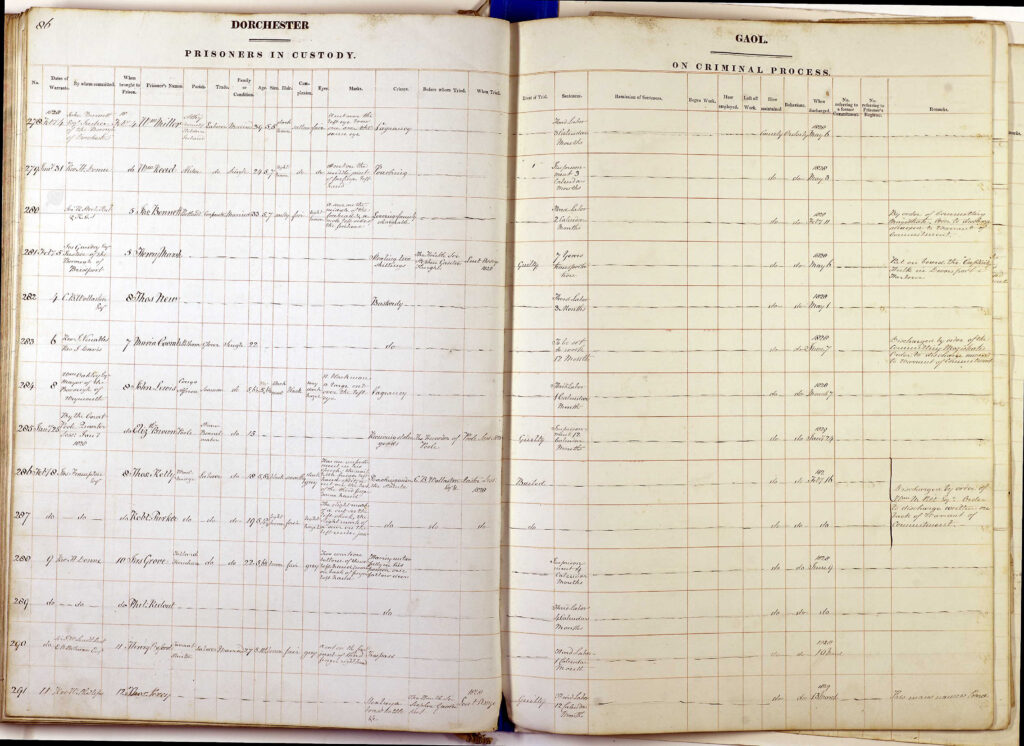

Lewis’s entry in the register of Dorchester Prison [Figure 1] identifies him as a native of ‘Congo’ and describes him as ‘a black man with a large cut over his left eye’. Little is known of Lewis’s early years. However, Admiralty records held at The National Archives reveal that in 1811, as a young man no older than 18, he joined the crew of HMS Mutine when she briefly docked in the Azores on her return journey from Rio de Janeiro to Portsmouth. On his arrival in Britain Lewis immediately deserted (along with several other crewmen) and disappeared from the historical record. Seventeen years later and now in his thirties we find him at Weymouth.

Lewis’s fleeting appearance at the by-election of 1828 adds to a growing body of work that continues to dispel what some historians have termed the ‘Windrush myth’, namely the misconception that people of African and Caribbean heritage did not migrate to Britain before the arrival of Empire Windrush in 1948. Lewis’s apparently leading role in the election ‘riots’ also serves as an example of Black political participation in early nineteenth-century England, which in recent years has begun to gain greater historical attention.

Given his maritime connections, it appears that Lewis was part of a motley group of sailors hired to support the campaign of Major Richard Weyland, the ‘Blue’ candidate at the 1828 Weymouth by-election. Weyland was standing thanks to the support of his wife, the dowager Lady Charlotte Johnstone, who possessed considerable property and influence in the constituency. Weyland’s opponent for the ‘Purples’ was Edward Sugden, a chancery lawyer and future Conservative lord chancellor.

At the previous general election in 1826, Lady Johnstone (as she was commonly known) helped ensure the return of her brother, John Gordon, for the four-member constituency. According to the historian and antiquarian, George Alfred Ellis, a notable feature of that election was its lawlessness due to the candidates’ use of hired ‘gangs of desperate individuals’. Reports in The Times suggest that Gordon’s extremely costly campaign (£40,000) relied heavily on the ‘powerful services’ of the sailors of Portland, who lived and worked on the rocky peninsula lying to the south of Weymouth.

![A picture of six men sitting in a room in a ship in scruffy nineteenth-century clothes. There is writing below the image titled The Sailor's description of a Chase & Capture: "Why d'ye see 'twas blowing strong, & we were lopping it in forecastle under in Portland Roads, when a sail hove in sight in the Offing; we saw with half an eye, she was an enemy's cruiser—standing over from Cherbourg, better she could'nt come, so we turned the hands up & drew the splice of the best bower [an anchor], but she not liking the Cut of our jib hove in stays; all hands make sail Ahoy; away flew the cable end for end & before you could say pease we had her under double reef'd top sails & top gallant sails, my eyes how she walked licking it in whole green seas at the Weather Chess tree & canting it over the lee yard arm pigs & live lumber afloat in the lee scuppers but just as we opened the bill standing through the tail of the race, by the holy! I thought she'd have tipt us all the nines but she stood well up under canvass, while Johnny Crapand was grabbing to it nigh on his beam ends so my boys we bowsed in the Lee guns, gave her a Mugian reef & found she had as much sail as she could stagger under, we came up with her hand over fist & about seven Bells she began to play long balls with her stern chasers, but over board went her fore top mast, her sails took aback & she fain would be off, but we twigging her drift let run the clew garnets ranged up to windward & gave her a broadside twixt wind & water as hard as she could suck it that dose was a sickner d—n the shot did she fire afterwards hard a starboard flew our helm & whack went our cathead into her quarter gallery with a hell of surge over board went her mizen mast in dashed our boarders & down came her Colours to the Glory of Old England & the flying Saucy with three hearty Cheers!!!! "— 7 January 1822](http://hopblog.monaghan.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/CRUIKSHANK-SAILORSDESCRIPTION-©-The-Trustees-of-the-British-Museum.-Shared-under-a-Creative-Commons-Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike-4.0-International-CC-BY-NC-SA-4.0-licence-709x1024.jpg)

The same tactic was employed in 1828, with the Dorset County Chronicle noting that Weyland’s Blues had again ‘called to their assistance a number of the hardy race of Portlanders’, describing them as men who ‘care little for the means by which they obtain their object’.

Weyland began canvassing vigorously from the start of February and shortly thereafter local newspapers reported election disturbances in the streets of Weymouth. Lewis appears to have been arrested on the evening of 8 February, before the official nomination of candidates which took place the following day. He was therefore in jail for the entirety of the polling.

According to a visiting magistrate, John Morton Colson, Lewis’s behaviour in prison was exemplary. Colson contrasted this with his riotous conduct ahead of his arrest, which the magistrate believed had been orchestrated by the Blues. In Colson’s view, the migrant sailor’s ‘ignorance and simplicity’ had been ‘taken advantage of by a cowardly and disigned [sic] party [i.e. Weyland’s election committee]’ who had plied him with drink. Writing two years after the fact, Colson blamed Weyland for corrupting Lewis and for plunging Weymouth into chaos and disorder during the subsequent poll.

Figure 4 – Map showing key sites of the Weymouth and Melcombe Regis By-Election of 1828. Borough boundaries based on TNA, T 72/11. Basemap: © National Library of Scotland

Polling took place in Weymouth and Melcombe Regis across ten days between 11 and 20 February (which was normal for elections before the 1832 Reform Act restricted the duration to two days). During the first days of the poll, Weyland’s election committee was reported to have stationed 300 Portlanders in front of Weymouth’s Guildhall to intimidate electors coming there to cast their vote for the Purples [see Figure 4].

Weyland’s opponent, Sugden, initially tried to secure a suspension in polling, after complaining to town officials that his rival had employed ‘foreigners’ (as he termed them) to win the election by ‘fraud and violence’. After his request was denied, on the third day of polling Sugden engaged his own small army of farm labourers from nearby Radipole to protect his electoral interests. This proved a pivotal moment in the election. Sugden’s supporters gradually gained dominance over key election sites, allowing their candidate to secure a comfortable majority by the end of polling.

Lewis meanwhile languished in Dorchester jail under a charge of vagrancy. Remarkably, official records suggest he was the only individual imprisoned for offences related to the by-election. This is despite the fact that hundreds of sailors and labourers (not to mention several election agents!) contributed to the ‘disorder’ of February 1828 and Weymouth’s mayor and magistrates threatened to draw up indictments against the worst offenders. This highlights the significance of Lewis’s case for those seeking to develop a wider understanding of racial attitudes within the nineteenth-century English legal system.

At the same time, Lewis’s ‘orderly and inoffensive’ conduct whilst incarcerated caused the prison authorities to raise a small subscription on his behalf. Furthermore, in the run up to his release from prison in March 1828, Colson organised for Lewis to serve as a cook’s mate aboard the naval frigate HMS Blonde that was preparing to embark for the Mediterranean.

After his discharge from the navy ‘with good character’ the following year, we know that Lewis was again arrested, this time for a petty theft he committed while destitute at Wolverhampton. It was this second conviction that prompted Colson to write three petitions on behalf of Lewis. It is these documents, held at The National Archives, which by chance provide us with most of the vivid detail of Lewis’s earlier career as a hired election ‘rough’.

After his release from prison in August 1830, Lewis served aboard two more naval ships. No record of his life after 1849 (when he would have been approaching his fifties) nor of his death (presumably in the middle years of the nineteenth century) can be found, though the author’s search continues…

Reduced from a four- to a two-member borough, Weymouth and Melcombe Regis survived as a constituency after 1832 and continued to be the site of violent contests for decades to come.

JC

Suggested Reading

H. Adi, African and Caribbean People in Britain: A History (2023)

K. N. Abraham & J. Woolf, Black Victorians (2023)

H. Wilson, ‘The Presence of Black Voters in the 18th and 19th Centuries’, History of Parliament (2022)

C. Bressey, ‘The Next Chapter: The Black Presence in the Nineteenth Century’, in G. Gerzina (ed.), Britain’s Black Past (2020), 315-30

D. Olusoga, Black and British: A Forgotten History (2016)

S. Farrell, ‘Weymouth & Melcombe Regis‘, in D. Fisher (ed.), The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1820-1832 (2009)

G. Gerzina, Black England: Life Before Emancipation (1999)

P. Fryer, Staying Power: The History of Black People in Britain (1984)

N. File & C. Power, Black Settlers in Britain 1555-1958 (1981)