Drawing on her first biography for the House of Commons, 1832-1868 project, our new research fellow Dr Naomi Lloyd-Jones looks at the behind the scenes involvement of the long-serving Conservative MP Cecil Forester in the electioneering activities of the Carlton Club and the murky world of electoral corruption.

George Cecil Weld Forester (1807-86), or Cecil Forester as he was known, was Conservative MP for the small borough of Wenlock for well over half a century, serving from 1828 until he succeeded to the peerage in 1874. An officer in the Royal Horse Guards, Forester was remembered as ‘the best looking man’ in the Commons, with a ‘handsome face and aristocratic figure’, and was a ‘favourite’ of ‘every fashionable salon’. He once appeared ‘in full regimentals … sword and all’ to cast a vote against the Whig government before heading off to a ball and, having served as groom of the bedchamber to his godfather George IV, was considered a ‘suave and polished courtier’. Objectified for his looks, Forester was mocked for his supposed lack of intellect and it was once rumoured that a junior Guardsman was willing to bet on his inability to spell. Long regarded a ‘confirmed bachelor’, his marriage later in life to the wealthy widow of one of the first MPs from an ethnic minority background, David Ochterlony Dyce Sombre, who was declared a lunatic at her family’s behest, became a cause celebre by drawing him into a protracted legal dispute with the Indian government.

This picture of Forester is in stark contrast to the one which emerges from the fallout of the notoriously corrupt 1852 general election. Aside from 1832, when he was pelted with mud and stones, Forester’s own campaigns for Wenlock were dull affairs and he went nearly three decades without facing a contest. Yet his entanglement in the murky world of electioneering, orchestrated through the Carlton Club, was revealed by evidence to a select committee which examined events in Norwich, prompted by the suspicious withdrawal of election petitions challenging the election result. This committee’s proceedings shed light on the role of London’s political clubs at elections, and on efforts by the parties to avoid the exposure of electoral corruption through a practice known as the pairing off or swapping of petitions.

The committee found that the Norwich constituency formed part of a ‘compromise’ between two solicitor agents, the Conservative Henry Edwards Brown and the Liberal James Coppock, who agreed to simultaneously withdraw eight petitions that challenged the seats of 10 MPs. When examined, Brown explained that he and Coppock believed it was a ‘waste of money’ to pursue a petition where in any consequent by-election the same party as before would emerge victorious. With a ‘very long list of petitions on both sides’, over a series of meetings each agent offered to ‘withdraw so-and-so’, to the point where it became a case of ‘batch against batch’. The committee warned that such activity, done under the ‘cover’ of the 1848 Election Petitions Act, risked a ‘public scandal’ – yet it remains something about which historians know comparatively little.

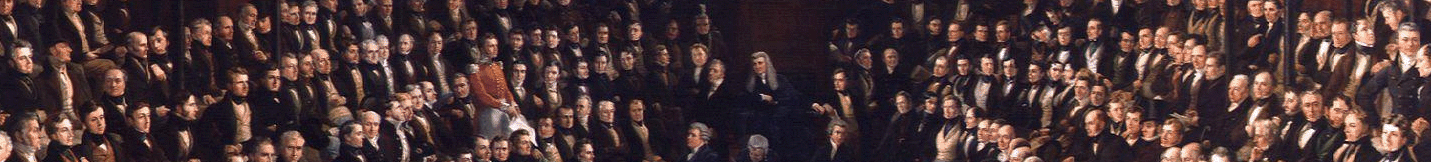

Further still behind the scenes, there was, reportedly, ‘a little coterie’ at the Carlton Club which many of those involved in the numerous electoral investigations held in 1853 assumed operated as a ‘committee’. According to Lothian Sheffield Dickson, who was defeated at Norwich and then saw his petition withdrawn without his consent, Forester and his fellow MP William Forbes Mackenzie were, together with Brown as agent, ‘known at the Carlton’ for the ‘principal management of elections’. When hauled before the committee, Forester was adamant that, far from there being a group ‘superintending elections’, he had taken it upon himself to discuss vacancies with several boroughs, maintain a list of those in need and do his best to ‘send them down’ candidates. Forester’s insistence that he was the ‘sole and responsible person’, however, seems at odds with one agent’s remark to the commission probing bribery in St Albans that it was common knowledge that ‘you go to the Carlton’ for a Conservative candidate and to the Reform Club for a Liberal or Whig.

Moreover, there had for decades been rumours that the Carlton Club administered a central election fund, possibly drawn from its membership fees. In 1852 accusations swirled that ‘Carlton gold’ had been ‘thrown about like dirt’ in the constituencies. Proving its existence was another matter, with various lines of questioning at the 1853 inquiries prompting rebuttals from witnesses. In both Cambridge and Barnstaple, the Conservative candidates, whose returns had been overturned, denied knowledge of ‘any fund whatsoever’, being raised by ‘subscription’ or used for their expenses. Forester, too, was resolute that he had ‘nothing to do with any money’, for either campaign or petitioning costs. Yet there were likewise agents who claimed to have been advised to apply to Forester at the Carlton for funds.

Also vague, and perhaps deliberately so, was the relationship between Forester and Brown. Brown was said to have advised clients that he had ‘one of those little dark rooms’ in the Carlton and various witnesses referred to having meetings in ‘Mr. Brown’s room’. However, there was confusion over whether Brown in fact shared a space with Forester, and the MP admitted that Brown – who as a non-member should not have had a separate room – had a key to Forester’s office, where he would have had access to electioneering papers. Forester throughout maintained that he personally had ‘never paired a petition, and never entered into any compromise’. He did nonetheless acknowledge that ‘people naturally will make the best bargain they can’.

During a Commons debate, the Radical MP Thomas Duncombe, who chaired the Norwich committee, urged that, with agents being ‘directed’ by the Carlton, any ‘indignation’ around a petition’s fate should be directed at ‘those who pulled the wires’. Forester’s frustration at the accusations was palpable, and, in a rare parliamentary speech, he explained that whereas Brown had ‘helped him’ with elections, Forester had never ‘consulted with him’ on or given him ‘directions’ as to the Norwich petitions. Forester doubled down on his line that he ‘had nothing to do with petitions’ and that ‘no Committee sat at the Carlton’. The controversy even threatened to boil over into a duel, with rumours in the clubs that the preliminaries had been agreed between Forester and Dickson, and that a duel was only averted at the ‘eleventh hour’ thanks to the ‘friendly intervention’ of another MP.

This scrutiny of Forester’s electoral skulduggery did not ultimately impact his parliamentary career, which ended with him holding the position of ‘Father of the House’ from March 1873 to October 1874, when he went to the Lords as the third Baron Forester. The 1868 Election Petitions and Corrupt Practices Act overhauled the process for challenging election results, handing constituency-based election judges the power to try petitions.

Further reading

S. Thevoz, Club Government: How the Early Victorian World was Ruled from London Clubs (2018)

N. Gash, Politics in the Age of Peel (1968)

C. Seymour, Electoral Reform in England and Wales (repr. 1970)

A. Cooke and C. Petrie, The Carlton Club 1832-2007 (repr. 2015)

K. Rix, ‘The Second Reform Act and the problem of electoral corruption’, Parliamentary History, 36: 1 (2017), 64-81