As part of a new infrequent series on the American Revolution and its connection to Parliament, Dr Robin Eagles explores the immediate background to the Revolution, and early Parliamentary debates surrounding it in February 1775.

At the beginning of 1775, pretty much every British politician agreed that something needed to be done about America, with many eager to find a way to reconcile both parties [Bradley, 19-20]. What they could not agree on, was how. Since the ending of the Seven Years War in 1763, relations between Britain and the American colonies had been difficult. In the aftermath of the war, there were large numbers of troops stationed in America, which annoyed many colonists, who viewed the presence of a standing army as a threat to their liberties. Matters became worse when George Grenville’s administration imposed the 1764 sugar duty and 1765 Stamp Act as a way of helping to pay for the colonies’ defence. In the aftermath of the latter, nine colonies convened the ‘Anti-Stamp Act Congress’ to condemn the ‘manifest tendency to subvert’ their rights and liberties. [Duffy]

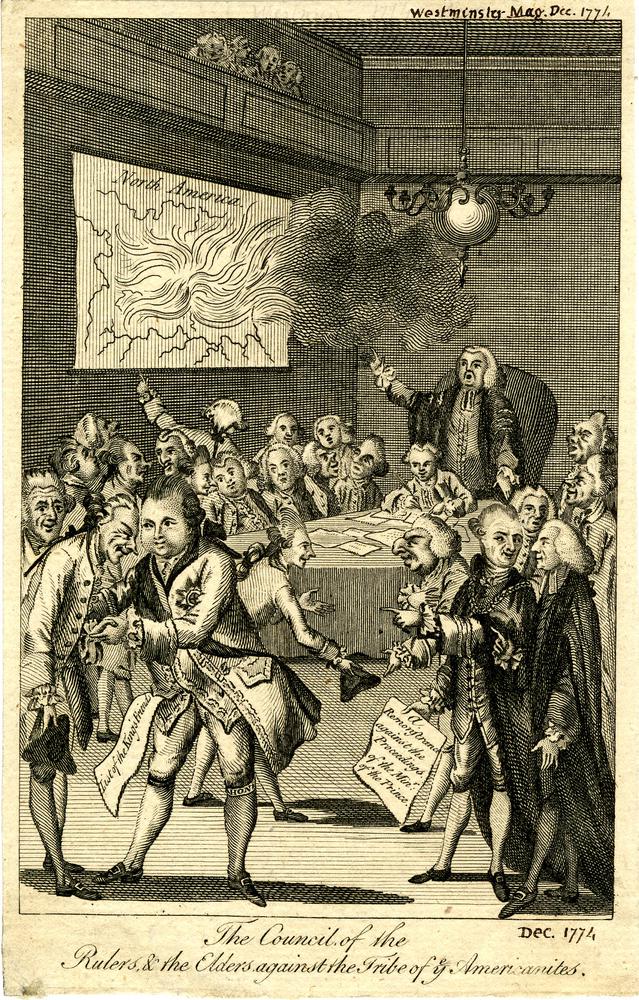

Repeal of the acts by the Rockingham administration in 1766 went some way towards resetting relations, but it was to prove a very brief lull. The Townshend duties of 1767 ramped up tensions once more and in March 1770 matters boiled over with the Boston Massacre. Three years later, in response to Britain granting the East India Company a monopoly on supplying tea to the colonies, a group of patriots in disguise boarded several ships in the harbour at Boston and dumped their cargo of tea into the water, in the so-called Boston Tea Party. This in turn led to more punitive action from Britain with the ‘Coercive’ or ‘Intolerable’ acts, which were aimed at punishing the state of Massachusetts for its involvement.

It was in this context, that on 1 February 1775, William Pitt the Elder, now in the Lords as earl of Chatham, rose to his feet to propose a Provisional Act for settling relations with America. Throughout the ongoing crisis Chatham and his followers maintained a consistent approach, sitting in between the government of Lord North, and the opposition Whig grouping led by the marquess of Rockingham, by arguing for a middle way in approaching the problem. America should remain a colony of Britain, it was contended, but its concerns should be addressed and concessions offered to help stabilize relations.

Chatham’s speech on 1 February, set out in detail his plans for how this might be achieved. He hoped that ‘true reconcilement’ would ‘avert impending calamities’ and the accord ‘stand an everlasting monument of clemency and magnanimity in the benignant father of his people’. In answer to those who thought he was offering the colonies too much by way of concession, he insisted it was ‘a bill of assertion’, stating clearly an ongoing relationship between mother country and colonies, in which Parliament would retain supremacy.

Well-known for his fiery (and often very lengthy) harangues, Chatham had couched his speech in terms of moderation and compromise, but after the proposed bill was laid on the table an immediate intervention by the earl of Sandwich ‘instantly changed this appearance of concession on the part of the administration’. Sandwich objected that the Americans had already committed acts of rebellion and turned on Chatham for introducing a measure which ‘was no less unparliamentary than unprecedented’.

Over the course of a debate that engrossed the Lords until almost ten o’clock at night and featured at least eleven lengthy speeches, the honours appeared relatively evenly matched. Speaking in support of Chatham was the gaunt figure of Lord Lyttelton, who praised him for his extensive knowledge and his good intentions and who, although not agreeing with everything Chatham was proposing, argued that his effort deserved a much kinder reception than Sandwich had given it. Lyttelton was then followed by an ‘extremely animated’ Lord Shelburne, one of Chatham’s principal acolytes, who feared that the interruption of supplies of corn that was one result of the collapse in relations between Britain and America, would lead to widespread rioting. He concluded with a start warning:

Think, then, in time; Ireland naked and defenceless, England in an uproar from one end to the other for want of bread, and destitute of employment.

Not all of Chatham’s erstwhile colleagues were so supportive. The duke of Grafton, who had served with Chatham when prime minister and succeeded him in the office, complained about the ‘very unparliamentary manner in which the noble earl had hurried the bill into the House’. He also found fault with Chatham lumping so many different themes together within the one bill. They ought, he felt, to have been treated separately. His intervention later attracted a rebuke from Chatham, who was amused at being accused of rushing the bill into Parliament, when the crisis called for swift action, which he argued the government was incapable of doing.

After Sandwich, probably the fiercest critic of Chatham’s propositions from the government side came from Earl Gower, who was said to have risen to his feet ‘in a great heat, and condemned the bill in the warmest terms’. He was particularly irritated by what he perceived as Chatham’s decision to sanction the ‘traitorous proceedings of the [American] congress already held’ but also his suggestion that it be legalized ‘by ordaining that another shall be held on the 9th of May next’. When Chatham rose to answer Gower’s criticisms, Gower could not stop himself from making further interventions as the atmosphere in the Lords collapsed into general name-calling. Chatham’s final contribution to the day’s mud-slinging was to accuse the ministry’s conduct over the past few years of demonstrating:

one continued series of weakness, temerity, despotism, ignorance, futility, negligence, blundering, and the most notorious servility, incapacity, and corruption…

The final contributions of the day were attempts at moderation by the duke of Manchester and Chatham’s cousin, Earl Temple. Manchester feared that a civil war would end in the destruction of the empire, as had happened in the case of Rome and wished only ‘that one sober view should be taken of the great question, before perhaps we blindly rushed into a scene of confusion and civil strife’. Temple, meanwhile, pointed the finger of blame for the current problems at the repeal of the Stamp Act, but most of all appealed to the Lords not to reject out of hand Chatham’s propositions, which he believed were thoroughly well intentioned.

In spite of Temple’s last minute effort to persuade his colleagues to grant time to Chatham’s ideas, when the House divided the government secured a sizeable majority, voting to reject the bill by 68 to 32. A few days later, on 9 February, Massachusetts was declared to be in a state of rebellion. It was, of course, just the beginning of an affair that would ultimately result in all-out war a few months later.

RDEE

Further Reading:

James E. Bradley, Popular Politics and the American Revolution in England (1986)

Cobbett, Parliamentary History xviii (1774-1777)

Michael Duffy, ‘Contested Empires, 1756-1815’ in Paul Langford, ed. The Eighteenth Century (2002)