In October 1788, George III fell ill with an unknown ‘malady’ which rendered him unable to fulfil his duties as sovereign: the beginning of the king’s famous ‘madness’. In the latest post for the Georgian Lords, we welcome Dr Natalee Garrett, who considers the role of Queen Charlotte during the period of the king’s illness, and more broadly.

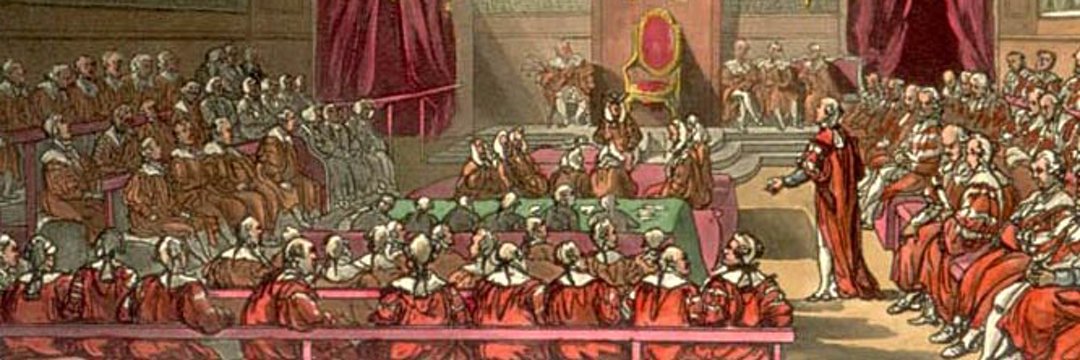

As the Prince of Wales was 26 years old, it was assumed that he would be made regent during his father’s incapacity. Although Prime Minister William Pitt agreed that the Prince was the obvious choice for a regency, he was wary of taking this step because of the younger George’s well-known friendships with Opposition politicians. The Opposition, led by Charles James Fox, clamoured for their ‘friend’ to be made regent on the assumption that George III would not recover. Meanwhile, Pitt and the government stalled, insisting that a full regency was unnecessary, as the king would recover in short order. Instead, the government suggested a restricted regency, which would limit the prince’s powers and place some responsibility in the hands of the queen: Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz. This approach was immediately viewed by the Opposition and their supporters as unconstitutional, and as an attempt by Pitt to control the country through Queen Charlotte.

Although Queen Charlotte had never shown any interest in influencing British politics before, she suddenly found herself saddled with a reputation for political meddling. Such was the belief that the queen was colluding with Pitt that her second son, the duke of York, confronted her and warned her that if she sided with Pitt, it would cause a falling out with the Prince of Wales.

Although the Prince was often described within the family as the queen’s favourite child, their relationship certainly cooled in the winter of 1788-89. Courtiers were shocked by the way the two eldest princes treated their mother at this time. William Grenville remarked to his brother, the marquess of Buckingham, ‘I could tell you some particulars of the Prince of Wales’s behaviour towards her [the queen] within these last few days that would make your blood run cold.’ [Buckingham and Chandos, 68] Charlotte Papendiek, whose family were in service to the royal family for decades, recalled that the Prince of Wales was ‘very heartless’ as he ‘assumed to himself a power that had not yet been legally given to him, without any consideration or regard for his mother’s feelings.’ [Papendiek, 15] Meanwhile, Queen Charlotte was deeply affected by the king’s erratic behaviour and the seriousness of his illness; one of her attendants, the author Frances Burney, witnessed her pacing in her rooms and crying ‘What will become of me?’ [Burney, 293]

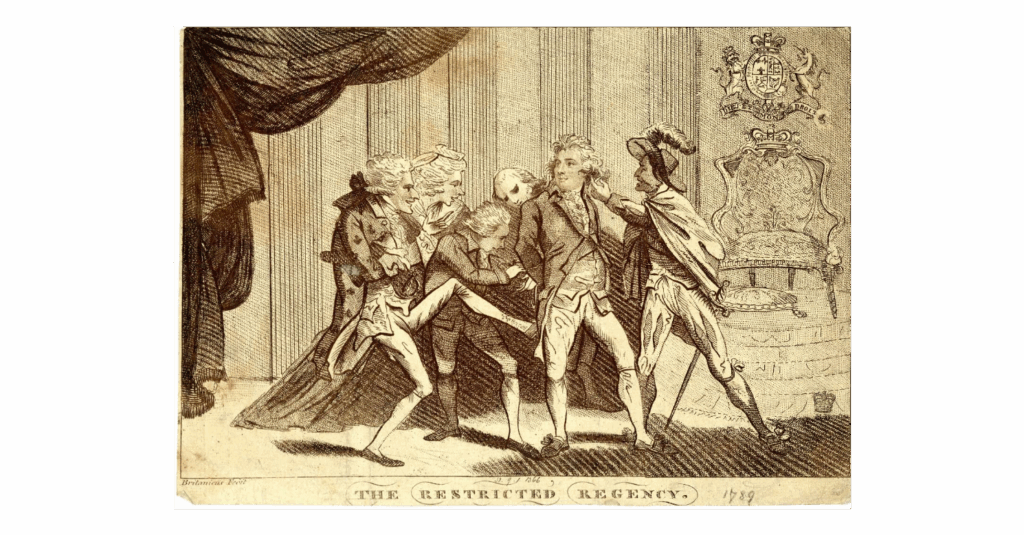

In the press, the queen’s reputation was dragged through the mud by newspapers and satirical prints produced by supporters of the Prince of Wales and the Opposition. One satirical print portrayed the queen looking on with satisfaction as her son was attacked by British and foreign politicians.

Another showed her stepping on the Prince of Wales’s emblem as she left the Treasury with Prime Minister Pitt. The Morning Chronicle cast aspersions on her devotion to her husband, claiming that she was motivated by a desire to take possession of diamonds worth thousands of pounds, not by any wish to help the king.

(c) Trustees of the British Museum

When it was suggested that the queen would take charge of the royal household and privy purse in a restricted regency, The Times published a comment made by Opposition MP Edmund Burke in Parliament that he ‘by no means thought her [the queen] the most proper person to be entrusted with the giving away of such an immense sum of money.’ In January 1789, as plans for a regency became more urgent, Earl Harcourt recorded a remark made by Burke during a debate: ‘The question is now come to this. Is it to be the House of Hanover, or the House of Strelitz that is to govern the country?’ [Harcourt, 167] For all its hyperbole, Burke’s question had explicitly marked Queen Charlotte, previously a queen of excellent reputation, as a threat to the established order.

Charlotte wasn’t the only woman whose reputation was tarnished by accusations of political meddling in Georgian Britain. Her mother-in-law, Augusta, Princess of Wales, was accused of influencing her son, George III, for decades. There were also long-term rumours of a supposed affair with the former Prime Minister, the earl of Bute. Horace Walpole recorded that during the princess’s funeral procession to Westminster Abbey, Londoners ‘treated her memory with much disrespect.’ [Walpole, 17] Anxiety over the influence of women in politics was expressed in the contemporary phrase ‘petticoat government’, which suggested that male political leaders were being unduly influenced by women, be they mothers, wives, or lovers.

Most critiques of Queen Charlotte portrayed her as a willing follower of Pitt’s schemes, rather than an active agent in her own right, but the queen was not afraid to stand up for herself and the king when necessary. In January 1789, a further scandal of the Regency Crisis unfolded after the queen insisted that a more positive note be included in the king’s daily health bulletin. The bulletins rarely varied, but in early January, Charlotte was informed by one of the royal physicians that the king seemed slightly better. One of her attendants, Lady Harcourt, recorded that when the head physician argued that he saw no improvement, the queen overrode him and insisted that the phrase ‘His Majesty is in a more comfortable state’ be added [Harcourt, 125-8]. When the Opposition heard of this, they insisted on a government inquiry into the credentials of the king’s physicians: their ambition for power through the Prince of Wales depended on George III’s illness being permanent and any suggestion to the contrary was unwelcome.

Fortunately for Queen Charlotte, just as the government was beginning to put in place a restricted regency in February 1789, George III began to show signs of sustained improvement. By March, he was sufficiently well to make a formal speech in Parliament announcing his recovery. Queen Charlotte led the nation in celebrating his recovery, organising Thanksgiving services and ordering official commemorative gifts for loyal attendants. Despite this happy ending and the ensuing national celebrations of the king and his loyal consort, the spectre of the Regency Crisis would taint Queen Charlotte’s public reputation for the rest of her life.

NG

Further Reading

Duke of Buckingham and Chandos, Memoirs of the Court and Cabinets of George the Third, vol.2 (Hurst & Blackett, 1853).

Charlotte Papendiek, Court and Private Life in the Time of Queen Charlotte: Being the Journals of Mrs Papendiek, Assistant Keeper of the Wardrobe and Reader to Her Majesty, Edited by Her Granddaughter Mrs Vernon Delves Broughton, vol.2 (R.Bentley & Son, 1887).

Frances Burney, Diary and Letters of Madame d’Arblay, Author of Evelina, Cecilia etc, ed. Charlotte Barrett, vol.4 (H. Colburn, 1842-6).

[Anon.] The Restricted Regency (1789).

Morning Herald, 5 January 1789.

The Times, 7 February 1789.

The Harcourt Papers, ed. Edward William Harcourt, vol.4 (Oxford: J. Parker & Co., 1880).

Horace Walpole, Journal of the Reign of King George the Third, from the year 1771-1783, ed. John Doran (1859).

Report from the Committee Appointed to Examine the Physicians Who Have Attended His Majesty During His Illness, Touching the Present State of His Majesty’s Health, 13 January 1789 (John Stockdale, 1789).