Ahead of next Tuesday’s Parliaments, Politics and People seminar, we hear from Dr Alex Beeton. On 10 December he will discuss the creation and use of the Lords Journals during the 1640s.

The seminar takes place on 10 December 2024, between 5:30 and 6.30 p.m. It is will be hosted online via Zoom. Details of how to join the discussion are available here.

Should the fancy ever strike a scholar to investigate the early modern House of Lords, they would know where to look: the Lords Journals, conveniently available on British History Online. These mammoth works, kept by the clerks and printed in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, are the official record of the upper House.

The Lords Journals acted as minute books of decisions made by the peers and are foundational to parliamentary history. So important are they that it is easy to assume that they are the record of the Lords in its totality. In one important sense such an assumption is correct. The House of Lords was a court of record, that is a court whose decisions had to be enrolled and accessible. As such, the journal had a unique legal importance unmatched by other records of Lords proceedings.

Sir Simonds D’Ewes, an important parliamentary diarist in the seventeenth century, noted in January 1642 during a heated debate about events in the upper House that the Commons:

may take notice of anything that is upon record, of which nature the Journal of the peers house is and may be produced as evidence in any court of Westminster the next day after it is entered.

The Journal was the official record of the Lords and has a position of primacy in the minds of historians, yet was this perception shared by those in the early modern period? The answer appears to be no. Evidence from the 1640s suggests that those living through the seventeenth century had a much broader conceptualisation of what made up the record of the Lords and included a mixture of official and semi-official texts.

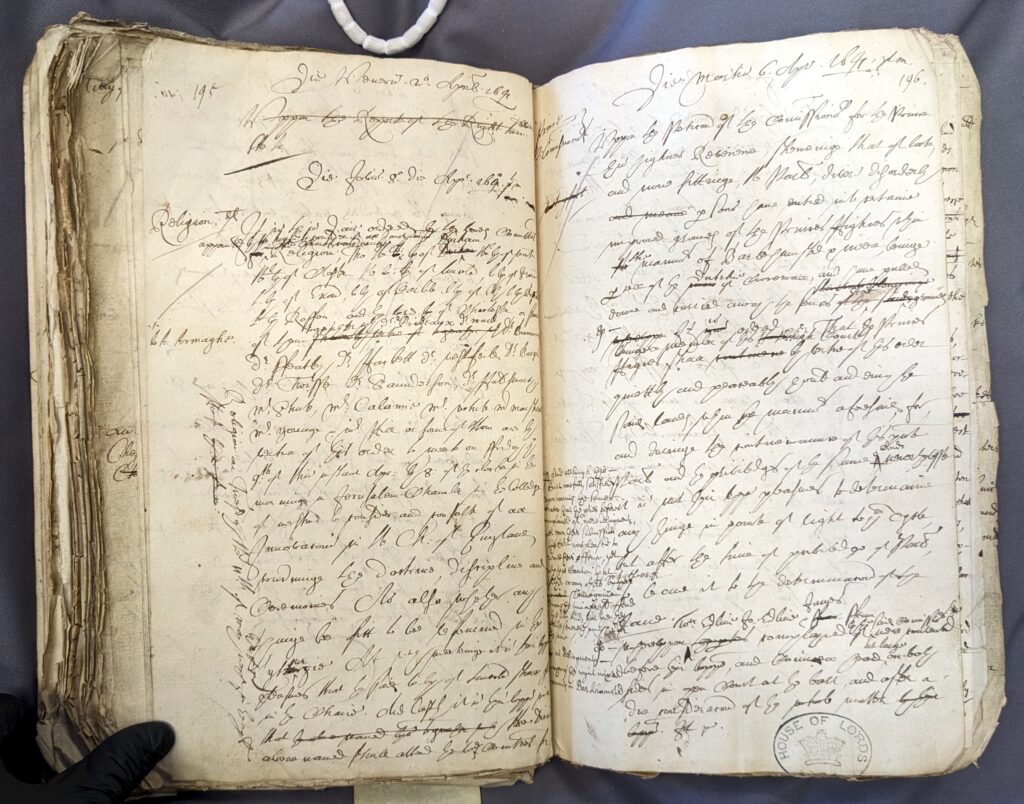

This point can be evidenced by examining the manuscripts of proceedings kept by the Lords’ clerks and particularly the marginalia within them. Alongside the Journals, these officials created Books of Orders (which contain orders made by the House) and minute books (the so-called Scribbled Books kept by the Clerk of the Parliaments and Manuscript Minutes kept by his Deputy) which essentially acted as draft Lords Journals, being used to create the more perfected version later.

These three types of manuscripts, and other materials kept in the Main Papers at the Parliamentary Archives, all contain information not found in the Journals. This outcome is to be expected. As anyone who has used them will know, the Journals are skeletal. They did not contain details of debates or (usually) individual interventions for reasons of brevity and to protect the freedom of the peers to debate matters freely. They also observed the norms of early modern recordkeeping, seen in the records of town corporations, trade companies, or the Privy Council, by presenting the body in question as driven by consensus and characterised by harmony between its members.

Concerns with streamlining and presenting the Lords in a particular light meant that a huge amount of information about events in the upper House was left out of the Journals. This was certainly to the detriment of the casual reader as the Lords appears to have been, in reality, quite entertaining, with fiery exchanges between irascible peers, lords chatting near the fire to escape the cold and boredom, and earls using the aisles as urinals.

Anyone trying to figure out what had happened in the Lords would therefore have been struck by a simple fact – the Journals were not always terribly useful. The Books of Orders, for example, regularly contain items which are either abbreviated in the Journals or only mentioned in passing. There would therefore have been a great incentive for contemporaries to make use of these semi-official sources.

This point leads to two linked questions: did people make use of them and what status did they enjoy? The evidence from the manuscripts themselves, especially indexing and the frequent marginalia on the pages, suggests a resounding yes to the former question. Clearly, contemporaries were aware of the need to track business not only over a period of time, but over a number of manuscripts with the clerks often noting next to items where other, relevant, entries were to be found.

Contemporaries also appear to have been interested in the fuller proceedings of events in the Lords, with a booming interest, stretching back to earlier parliaments, in the manuscript circulation of reporting about parliamentary affairs. This interest at times took them beyond the Journals to the much fuller semi-official sources.

However, it is much less easy to determine the status of these sources. They clearly were significant: the Books of Orders were orders of the House; the clerk used the Scribbled Books to create books of parliamentary precedents for future use; and all the manuscripts contain information of proceedings written by the Lords’ principal clerk or his assistants.

Yet the Scribbled Books and Manuscript Minutes were also very clearly unofficial. There appears to have been no method by the Lords to vet these materials (in contrast, the Lords had several mechanisms to check the Journals, including the subcommittee of privileges which intermittently checked the Journals during the 1640s). They were also, to some extent, the private property of the clerks who treated them as such, scrawling graffiti on them and even occasional disparaging remarks about the Lords and their decisions.

All told, terming them semi-official (though such a description does not feel quite right for the Books of Orders) seems broadly accurate and an awareness of their importance shows that it is necessary to incorporate them into a revised understanding about what constituted parliamentary records in the seventeenth century.

AB

The seminar takes place on 10 December 2024, between 5:30 and 6.30 p.m. It is will be hosted online via Zoom. Details of how to join the discussion are available here.