Ahead of next Tuesday’s Parliaments, Politics and People seminar, we hear from Professor Paul Seaward, former Director of the History of Parliament. On 29 October he will discuss Dining in the Palace of Varieties: institutional culture, society living and party management in the Victorian House of Commons.

The seminar takes place on 29 October 2024, between 5:30 and 6.30 p.m. It is fully ‘hybrid’, which means you can attend either in-person in London at the IHR, or online via Zoom. Details of how to join the discussion are available here.

Our histories of politics rarely engage with so mundane a subject as dinner. Politics, we like to think, consists of a great clash of beliefs spiced with personal ambition; parliamentary debate is a matter of the contest of ideas enlivened by powerful rhetoric. Like any other human activity, however, the conduct of politics rests not just on the ideological commitments, but also on the personal habits, convenience and energy of individuals. Furthermore, the operation of great institutions relies on a host of complex and interlocking arrangements, an underlying social ecology that is sensitive to subtle change and easily prone to collapse.

The history of the ‘dinner hour’ in the late nineteenth century provides a window into the relationship between politics and the social and domestic habits of politicians in a period of rapid change.

While, impelled by electoral reform, the structures of party organisation entrenched themselves ever deeper in the political process, the Irish party pioneered practices of political disruption that forced governments to accelerate their dominance of the parliamentary agenda. Meanwhile, a broadening of the political and social elite by the end of the century started to alter the conventions and rhythms of London society. For those managing parliamentary politics one of the most obvious points of stress in all this was the crucial period of social interaction (and also parliamentary business) in the mid-evening, the dinner hour.

For the already grand or the seriously ambitious, the focus of everyday life during the London season (which coincided with the climax of the parliamentary session) was dinner, a matter of conspicuous feeding and competitive socialising that mixed the worlds of society and politics.

Unfortunately, the curious habit of the United Kingdom Parliament beginning its daily proceedings well into the afternoon, and continuing them way beyond the time most decent people were tucked up in bed, meant that dinner inconveniently came in the middle of the House of Commons’ daily timetable. The risk was that between the hours of around 8 and 10 or 11 p.m. Members would stream away to more enticing appointments, creating a constant threat that the House would lose its quorum and end up adjourning prematurely, with the business set down for the day forcibly abandoned.

This was a nuisance for lots of people, but especially so for the stressed and chronically underpowered government whips, whose job it was to try to ensure that government legislation was safely processed through the House. Their task became more essential and more difficult as Irish members embarked in the 1870s and 1880s on their deliberate campaigns of disruption, and other opposition politicians later followed them in adopting ruthless parliamentary tactics.

For the whips, the sharpening of opposition tactics coincided with a change in the nature of their Members: they complained that the busy professionals and businessmen who (they claimed) formed a growing proportion of MPs were less and less willing to while away the evening hours in the House when they had more important things to attend to elsewhere.

The issue had always been closely related to the provision of dining facilities enticing (but also cheap) enough to encourage Members to stay put during the evenings. Dining rooms had been provided in the new palace, which had been rebuilt gradually since the fire of 1834, but many Members were disappointed by the quality of the food and service provided.

For those in charge it proved extremely difficult to run a restaurant profitably when it operated for only four days a week, around half the year. Subsidies (to the immense annoyance of some, for whom it was the thin end of the wedge of a professionalised political system) were required to fill the profitability gap.

One answer to the whips’ problem was a proper adjournment of the House during dinner time. It would mean that Members would not be required in the early evenings, and that the whips would not have to worry about the collapse of business. It was a theoretically attractive solution, which the whips pushed on the government in 1902, claiming that the change would suit professionals and businessmen who were now reluctant to go into politics. When it was debated the Opposition poured scorn on this argument, and when the new system was tried in 1902 it proved (as they predicted) unworkable.

If it had worked, it would probably have made running a dining room in the Palace completely impossible. But meanwhile the increasing importance of the House of Commons itself as a social destination, as part of the ‘Season’, was rescuing the refreshment rooms, as they were called, from insolvency.

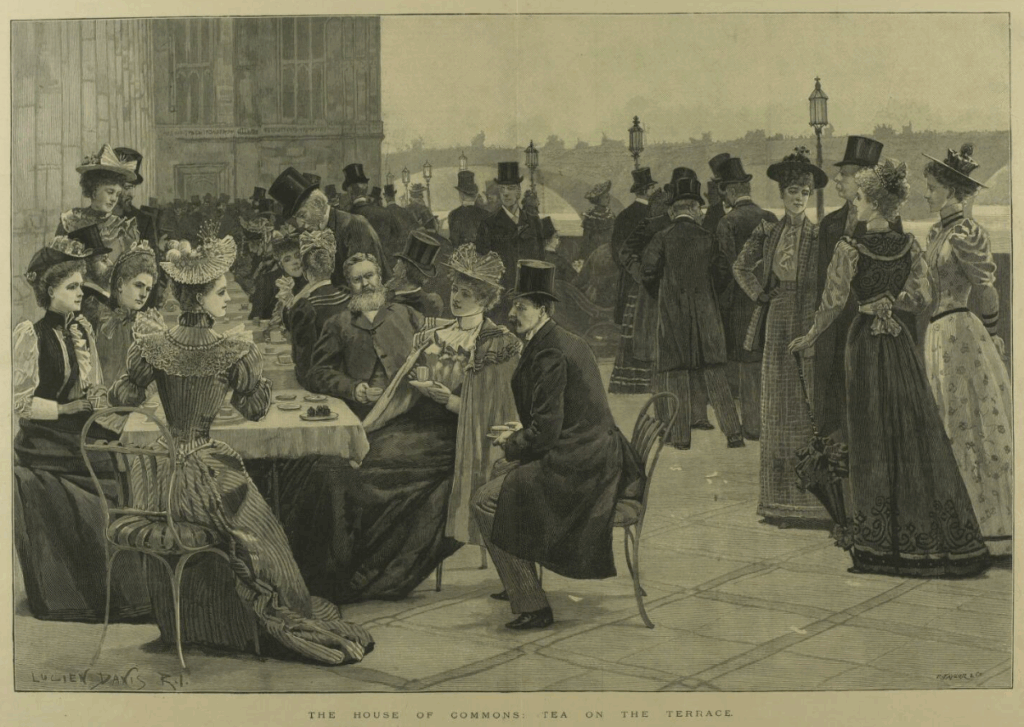

From the 1880s onwards the Terrace became renowned as a pleasant venue for afternoon tea or early evening drinks, and was thronged with Members entertaining (especially) their female friends and relatives while they were within hailing distance of a division. Quite soon too came the development of private dining rooms where Members could hold their own dinner parties rather than leaving the Palace of Westminster. By the beginning of the twentieth century such private dining was helping the House’s catering service to be profitable.

It was not a solution to the whips’ problem – which was overcome more by a changing understanding and acceptance of the obligations of party politicians – and yet by making Parliament more central to the social, as well as the political, life of an expanding elite it helped along that changing understanding of how a new type of democratic, but still highly elitist, politics might work in practice.

PS

The seminar takes place on 29 October 2024, between 5:30 and 6.30 p.m. It is fully ‘hybrid’, which means you can attend either in-person in London at the IHR, or online via Zoom. Details of how to join the discussion are available here.