Our Parliaments, Politics and People seminar is back for the winter term. At next week’s seminar Dr Lauren Lauret of University College London will discuss how politicians who started their careers in the colonies shaped the culture of Dutch Restoration politics between 1815 and 1840.

The seminar takes place on 16 January 2024, between 17:30 and 19:00. It is fully ‘hybrid’, which means you can attend either in-person in London at the IHR, or online via Zoom. Details of how to join the discussion are available here

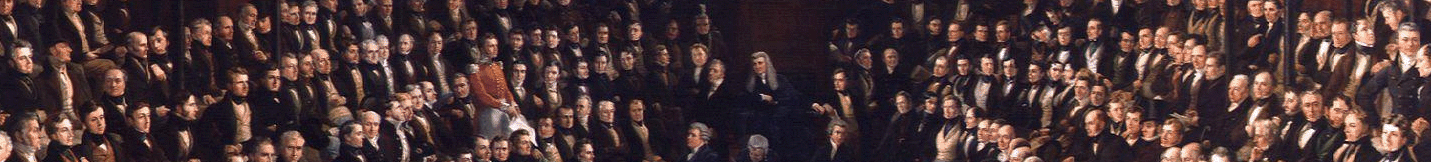

At first sight, Daniël van Alphen’s (1774-1840) parliamentary career confirms older studies about boring parliamentary elections in Restoration Netherlands: his family name and inherited wealth entitled him to his parliamentary seat for life. Before arriving at the political stage, however, Van Alphen had worked as a naval officer, civil servant and merchant in Soerabaja, Yogyakarta and Semarang between 1797 and 1808. After re-migrating to his birth country, he belonged to the first cohort of 110 MPs elected to the newly established Second Chamber in 1815, the lower house of the bicameral States General.

Up until now, Daniël van Alphen is best known as one of the few MPs critical of King William I’s Restoration government (r. 1815-1840). Yet, in opposing the Cabinet, Van Alphen more than once faced ministers with a similar background to his own. In the early 19th century, colonial experience was more common among the executives in government than among MPs. This seminar puts Van Alphen’s actions in a new light, because it repositions him among his colonial peers in the Netherlands shaping Restoration politics as cabinet minister or MP.

Restoring Kingdom and Colonies

In late 1812, Daniël van Alphen had two aims in mind when he rented no. 6, Windsor Terrace, a house at the edge of London on Islington’s City Road. Firstly, he hoped to reclaim the personal fortune he had deposited with the Dutch government in Java’s capital, Batavia, before repatriating to the Netherlands in 1809. Since that year, however, England had taken over control of the archipelago (1811), and more recently France had incorporated the Netherlands as well as Java (1812). Van Alphen hoped that persuading senior English politicians to acknowledge his claim on the deposit would ‘secure my affairs in the East’.

Secondly, he tried to persuade the English to re-establish their authority over the island of Java, albeit with the exiled Prince of Orange, later King William I, as their governor-general. The delegation ‘would no doubt succeed’, Van Alphen wrote to the Dutch envoy in London, ‘as it was in the interest of Great Britain to possess Java in tranquillity and without much expense’. Despite all the efforts of Van Alphen and his friends in London, it was not until the Congress of Vienna (1814-1815) that the British decided to return some of the former Dutch colonies to the United Kingdom of the Netherlands.

Van Alphen addressed extensive notes on the Netherlands Indies to the leading politicians of the moment, G.K. van Hogendorp and A.R. Falck. Neither Van Hogendorp nor Falck had been to Java, but they had extensive colonial family ties. Falck was the son of a Dutch East Indies Company (VOC) merchant and board member who had represented the Company in Bengal, and Van Hogendorp’s father and brother had both emigrated to Java. Van Alphen presented Java as ‘a colony of the highest importance and of unaccountable resources’ to Van Hogendorp.

To Falck, Van Alphen appealed to the powerful memory of the VOC and the opportunity to revive its activities once the colony was back under Dutch control. ‘Centuries will pass, empires destroyed, and peoples civilised through force and injustice, but among the Oriental peoples the memory of the prestige, pomp, loyalty and righteousness of the old Dutch name and the East India Company will never fade’.

Van Alphen’s words landed on fertile ground, as the colonies became an integral part of the new state. Van Hogendorp even used the colonies to overrule the Southern members in the constitutional committee arguing for proportional representation in the Houses of Parliament. Van Hogendorp insisted on taking the colonial territories into account, on which basis the size of the (Protestant) Dutch population would outnumber the (Catholic) Belgian South by two to one. The Southern delegates backed down and agreed to 55 MPs for each half of the Kingdom in the Second Chamber. King William I ennobled Van Alphen in 1815, signalling the incorporation of the colonial elite into his circle of patronage.

Almost instantly, the economic role of the colonies in the restoration state became apparent, when the King imposed tax increases on sugar imported from the Netherlands Indies in 1816. Van Alphen responded in a long letter to the King outlining his objections to the new indirect taxes, a first sign that his ennoblement had not turned him into the subdued servant the King was looking for.

A clear indication of the King’s trust in colonial men came when he appointed C.Th. Elout, responsible for the handover of the Netherlands Indies from British to Dutch control (1816-1819), as his Treasurer in 1822. Elout protested, claiming ‘inexperience in everything resorting to governing finances’, which the King refuted by stating that Elout’s ‘credentials as commissioner-general of the East Indies enabled you to meet my expectations within short notice’.

The King’s servants? Van Alphen vs. Elout

Van Alphen and Elout found themselves on opposite sides in the core debate between parliament and government during the Restoration period: the King’s desire to decrease parliamentary control over his expenses. In 1821 the King submitted a bill to parliament aimed at generating money by way of a state domain bank issuing lotteries. The royal domains served as the bank’s pledge. Van Alphen declared the bill’s principle to be ‘vile and dangerous’ and believed a ‘crystal-lined framework’ ought to enshrine the state’s finances and its administration.

A large majority agreed with Van Alphen, and MPs rejected the bill by 75 to 20 votes. At this point, William I turned to the colonial politician on the other side of the debate: newly appointed minister of finance Elout. The King simply declared he was determined to execute this plan even ‘without the cooperation of the States General’. Within a month Elout executed the King’s wish by dividing the original bill into separate steps. Elout’s proposed ‘amortisation syndicate’ was a tool by which the government could control the state’s debt. Like other critical MPs Van Alphen voiced some minor objections and voted against the installation, but failed to point out the true ramifications of the syndicate: millions of guilders leaked away from the treasury without any parliamentary scrutiny.

Removed from the public debating floor, the Amortisation Syndicate proved a reliable if not lucrative investment. Van Alphen offered to buy his daughter and son-in-law shares in the Syndicate even though ‘it only gave 450 guilders of interest for f10.000’ in 1824. And the King used it as a private tool to exercise his royal prerogative in colonial affairs: by far the largest amount of money (f20.7 million) the Syndicate spent went towards the Java War (1825-1830).

In short, Elout’s direct involvement in establishing the Amortisation Syndicate and Van Alphen’s ambivalent relationship with its existence, position both colonial politicians at the heart of a defining institution of the Restoration regime. Elout’s colonial experience had qualified him to give the royal financial system the final push at its inception, whereas Van Alphen’s principled opposition to such opaque financial schemes did not prevent him from benefiting from its speculations for the sake of his family’s fortune.

LL

The seminar takes place on 16 January 2024, between 17:30 and 19:00. It is fully ‘hybrid’, which means you can attend either in-person in London at the IHR, or online via Zoom. Details of how to join the discussion are available here