Continuing our series reflecting on the Organise! Organise! Organise! conference hosted by Durham University and supported by the History of Parliament, guest blogger Dr Helen Sunderland, a historian based at the University of Oxford, discusses the new directions of research that were presented and considers what might be next for political history.

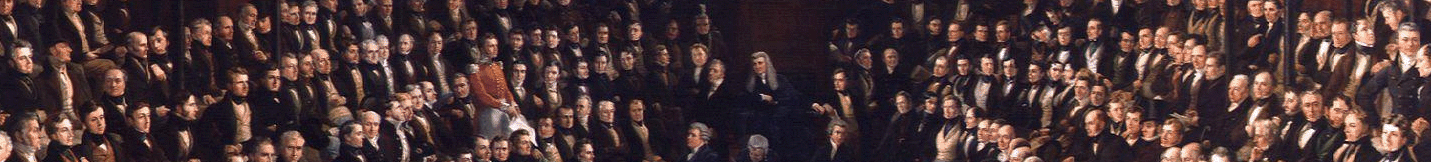

Two packed days at the Organise! Organise! Organise! conference at Durham University last month showcased the vibrancy of new research in British and Irish political history from 1790 to 1914. From the visual culture of reform politics to the tactical choreography of political meetings, countless papers illuminated not just how politics was thought about or communicated but how it was done.

As Katrina Navickas set out in her fantastic keynote, histories of political practices are transforming a field that still looks to the (no longer) new political history for its grand narratives. Studying the practices of politics refocuses our attention on behaviours not identities, the collective not the individual. In this vein, Navickas explained, political organising allows us to think across low and high politics, to bring together social histories of politics in the everyday and the history of ideas. Its strength lies in its versatility.

Photo © Tate

Recentring political practices makes us more attentive to the material constraints of political action, as speakers highlighted in important ways. In their paper on exclusive dealing, Richard Huzzey and Kathryn Rix suggested the political tactic was more likely to succeed in larger urban areas where the politically discerning consumer had more choice over where to spend their money. Chloe Ward’s paper on Victorian painters’ belief in art as a call to action expanded our discussions on the medium of the political message. But communicating this message wasn’t always straightforward, she explained. Artists were frustrated when their life-size portraits of social injustice were hung too high on gallery walls to give the most effective jolt to the art-consuming public’s conscience.

Political organisation also thrived on material inventiveness, like the plans for a ballot box that the radical parliamentary organiser Harriet Grote drafted with a Hertford carpenter in 1837, as Martin Spychal explored in his paper. The sheer size of petitions presented their own challenges. These could be solved, Henry Miller and Mari Takayanagi explained, with purpose-built wagons to transport ‘monster’ petitions to parliament or the resourceful requisitioning of an apple seller’s cart used to conceal the 1866 women’s suffrage petition for maximum impact.

![Mounted men, all fat, wearing yeomanry uniform, with the over-sleeves and steels of butchers, ride savagely over men, women, and children, slashing at them with blood-stained axes. Smoke, as from a battle, and bayoneted muskets, form a background, with (left and right) houses in whose windows spectators are indicated. They have a Union flag with 'G R' and crown, and a fringed banner inscribed 'Loyal Man[chester] Yeomanry—"Be Bloody, bold & Resolute" ["Macbeth", IV. i]— "Spur your proud Horses & Ride hard in blood" ["Richard III", v. iii].' On the saddle-cloths are the letters 'L M Y' above a skull and cross-bones surmounted by a crown. One man kicks a young woman who kneels beseechingly, clasping an infant, raising his axe to smite. The man behind him, his arm extended, shouts: "Down with 'em! Chop em down! my brave boys! give them no quarter, they wan't to take our Beef & Pudding from us!—& remember the more you Kill the less poor rates you'll have to pay so go it Lads show your Courage & your Loyalty!"](http://hopblog.monaghan.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/download-1.png?w=1024)

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Papers by Nicholas Barone on apathy in radical politics from 1790 to 1840 and Matthew Roberts on the changing feeling rules governing mid-Victorian parliamentary performance reflected the important ‘turn’ towards the history of emotions in studies of nineteenth-century politics. For a historian more at home after 1870, Laura Forster’s reappraisal of socialist conversion narratives and appeal to reimagine the history of socialist thought as a lifetime’s accumulation of intimate encounters struck a chord.

I think there’s much more that sensory history and the histories of the body can bring to our understanding of political organising. At least in the papers I heard, the history of disability was conspicuously absent. But if we go back to the first principles that Katrina Navickas outlined in her keynote, the actions that increasingly defined nineteenth-century politics – to meet, to be elected to a committee, to claim public space and the right to free speech – necessarily privileged certain bodies and excluded others.

We’re more attuned to thinking about the politics of the everyday, and this is a helpful reminder that political practices were often rooted in familiar rhythms and routines. Vic Clarke’s research on targeted advertising in radical publications like the Northern Star showed how medicines, beverages, and reading material were marketed in imaginative ways to a Chartist consumer audience. Everyday sites were reworked for political organising. According to Niall Whelehan, the Ladies’ Land League owed its success in Dundee in part to conversations involving Irish migrants in jute workshop dormitories. Mapping this across a neighbourhood, Katrina Navickas’s case study of the ‘radical locale’ of Dod Street elucidated how histories of socialist organising were embedded in working-class street and associational life in London’s East End.

Although more papers addressed radical than conservative politics, organising is a framework that holds across the political spectrum. In their introduction to Organizing Democracy: Reflections on the Rise of Political Organizations in the Nineteenth Century, Henk te Velde and Maartje Janse observe that as Western Europe grappled with questions about how to accommodate new modes of participation, ‘[p]olitical organizations offered an answer that, eventually, appealed to both political outsiders and members of the political establishment’. As Shaun Evans showed in his paper on the North Wales Property Defence Association, landowners in the 1880s and 1890s organised to resist land reform being replicated on the other side of the Irish Sea. If the practices of politics are to become a new framework across the field, we should welcome more research into how far competing political organisations did politics differently, and consider whether organisers’ activities, tactics, and timings varied in line with their political persuasions.

Refreshingly, the conference had a good range of papers on political organising across the four nations. Research by Erin Geraghty and Ciara Stewart unravelled moments of tension and cooperation between British and Irish women campaigners for suffrage and repeal of the Contagious Diseases Acts. At opposite ends of our period, papers on the politics of translation by Marion Löffler and Martin Wright illuminated the intricate transnational networks across generations of Welsh radical writers and fraught contests over how best to accommodate socialism to Welsh national identity.

My own work on schoolgirls’ politics aims to take the history of political practices into other unexpected places. As I argued in my paper, school mock elections expand our view of who counted as political organisers and where political organising happened. Looking at mock elections in three secondary and one elementary school in London and Manchester, I showed that girls were active electoral organisers amid the heightened partisan atmosphere of the 1909-11 constitutional crisis.

In mock elections, girls voted and stood for election years before women had the parliamentary vote. Schoolgirls learnt about politics by doing it. Their meticulous re-creation of the electoral process was an education for future citizenship and a radical claim to participation in the political nation. School mock elections help explain how women voters were assimilated into the electoral system after 1918.

Taking schoolgirls’ electioneering seriously helps us think differently about non-voter electoral culture. Mine was one of several papers challenging the idea that politics became more exclusionary as it became more democratic. School electoral activity represented a new, vibrant, and playful form of non-voter politics that, at least for girls and working-class pupils, only took hold on a significant scale from the turn of the twentieth century.

Fittingly for a conference on organisation, Naomi Lloyd-Jones did a stellar job putting the two days together. A huge thank you to Naomi, the conference sponsors, and all the speakers for such a stimulating event. I’m especially grateful to the History of Parliament Trust for their generous support for PGR and ECR attendees. I’m looking forward to continuing the conversations!

HS

Dr Helen Sunderland is a historian of children and young people’s politics in modern Britain and is based at the University of Oxford. She is currently writing a book on schoolgirls’ politics in England, 1870-1918.