Last month Durham University, supported by the History of Parliament, hosted the conference Organise! Organise! Organise! Collective Action, Associational Culture and the Politics of Organisation in Britain and Ireland, c.1790-1914. This conference saw historians declare that the study of long nineteenth-century political history was here to stay. Guest blogger George Palmer, PhD candidate at Emmanuel College, Cambridge, reflects on the conference.

In welcoming attendees to a conference that was both brilliantly organised and intellectually stimulating, Dr Naomi Lloyd-Jones (Durham) hailed the healthy turnout as evidence of a revival in long nineteenth-century political history. Though a decade ago it might have appeared that this period was becoming unfashionable and losing some of its best minds to the burgeoning field of twentieth-century history, few could make such a claim now. As a first-year PhD student for whom this was his first conference presentation and panel chairing, this is welcome news especially as doctoral study can feel isolating enough for any student. Indeed, the conference indicated that the future is bright as a healthy crop of early career and postgraduate speakers were heard and there was a great sense of conviviality as the generations mixed together. This was aided by very generous support from a number of sponsors, including the History of Parliament Trust, and our thanks must go to all those who enabled this important, agenda-setting conference to go ahead.

Proceedings began with a highly engaging keynote from Professor Katrina Navickas (Hertfordshire) who took the opportunity, very usefully, to lay out some ‘first principles’ of political history, before speaking on the importance of battles over meanings and ownerships of ‘space’. Conscious of the need to provide an answer to the ongoing question of ‘what next’ for the field as the ever-present shadow of the New Political History refuses to recede and the various ‘turns’ have done little to unite those charting a path forward, Navickas suggested that an idea of ‘practical politics’ might help give a greater sense of cohesion to historians of political culture. This idea of politics as embodied in action was something that many other speakers picked up on and helped to flesh out in their contributions.

Some key moments for me included Dr Henry Miller (Durham) conveying some of the fruits of his recent book on petitioning, attesting to the importance of the materiality of petitions in both reflecting and furthering political organisation. Dr Chloe Ward (Queen Mary) likewise spoke about the drive of Victorian artists to encourage an active response to social disadvantage in their viewers. Dr Helen Sunderland (Oxford) attested to the importance of school mock elections as a crucial activity for political identity-formation and Dr Kathryn Rix (History of Parliament) to that of regional party association in guiding and shaping local politics respectively. Such contributions sat alongside papers which were less about the ‘doing’ in politics and more about the intellectual and emotive motivations behind it. Professor Matthew Roberts (Sheffield Hallam) and Dr Laura Forster (Manchester) gave important papers on the intimate and affective subcurrents which helped structure and guide the expression of radical politics, while Olly Gough (Oxford) presented a wide-ranging portrait of progressive thinking about ‘character’ as expressed through voluntary association.

Consequently, what was presented across the two days was a rich and wide-ranging discussion across a huge variety of topics that spanned the entire period of c.1790-1914. Many responded imaginatively to Navickas’s initial charge and though tentative and perhaps not yet wholly formulated, the conference seemed to suggest that a new consensus and a convergence of different approaches to the study of political history in this period is starting to emerge. Future conferences will hopefully further incubate this newborn ‘practical politics’ approach and stimulate further thinking about the direction of our field as what is ‘new’ about the New Political History increasingly looks rather old.

The conference also served as a useful window into some of the broader trends in the field. The drive to increase a ‘four nations’ approach has undeniably achieved success, and it was encouraging to see so many papers dedicated to Scottish, Welsh, and Irish history. Nonetheless, it was also the case that many English papers strayed little beyond their primary subject-matter. Though a number of the contributions about radicalism were some of the finest of the conference, the period’s C/conservatives were notably underrepresented, and the century should not be seen as a ubiquitously radical one. Furthermore, though recent work has done much to elevate the role of religion within twentieth-century politics, during this conference the place of religion was at best peripheral. This reflects a broader hesitancy among historians in affording religion its proper place at the centre of what we are studying and is in much need of redress in future conferences.

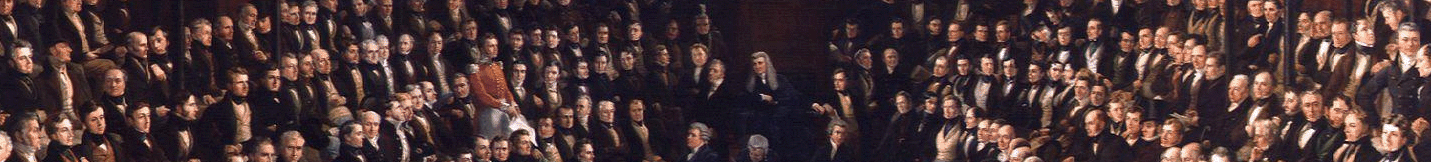

Nonetheless, the conference proved very encouraging in bringing together contributions from a wide range of disciplines, presenting a rich array of different visual and material sources, and in showing that older anxieties about the relationship between ‘high’ and ‘low’ politics are no longer so fraught. Rather, attendees were taken on a scenic journey that visited both Parliament and polling booth, marched alongside Chartists, doffed a cap to Anti-Corn Law Leaguers, traversed the Highlands of Scotland, sailed the Irish Sea to Belfast, and finally cast its net well beyond the shores of the British Isles as discussion of the politics of organisation in relation to empire closed the second day.

To a historian near the beginning of my academic journey, this conference was both greatly encouraging and deeply thought-provoking. Long hours trawling through source material in the library are made worthwhile when one is able to present pain-staking research to an interested and expert audience and to share thoughts and comments with one another in a mutually beneficial way. I hope that we will all meet again soon and build upon the tremendous success of this conference.

GP

George Palmer is a PhD candidate at the University of Cambridge, supervised by Dr Gareth Atkins. His project is entitled ‘Anglican Culture and English Public Life, 1870-1914’ and analyses the role that the Church of England played in shaping both local and national political affairs. He completed an MPhil in Modern British History at Cambridge in 2022 and before that studied for a BA at Hertford College, Oxford.